I wrote a post a few weeks back on what I called paradoxes in association management, which I defined as counter-intuitive practices that we must embrace if we want to be successful. Here's one:

Success comes when staff learns the language of members, not when members learn the language of staff.

This is one of the most obvious, but frequently one of the most difficult to embrace. In my experience, associations tend to develop two separate cultures--one defined by the members and the industry or profession they belong to, and another defined by the staff hired to manage the association, who most often are not members of the industry or profession the association represents.

In the best of cases, there is a large overlap in the Venn diagram describing these two cultures. In the worst of cases those circles barely intersect at all, the members and the staff understanding almost nothing about what makes the other tick.

And when that's the case, staff will often expend a tremendous amount of energy in order to "teach" members their definition of success. You must utilize our services in order to gain value out of this relationship. You must read our newsletters and attend our conferences. In this mindset the staff often loses track of the thing that matters most within those services--the content and its relevance to the member. Because association members generally have little loyalty to the vehicle of their association's newsletters and conferences. What they care about is the content that those vehicles are delivering--a commodity that is very difficult for a staff that has developed a non-intersecting culture to define and deliver.

It's not enough to promote a conference as having "great education and networking." Or a newsletter as containing "information of direct relevance to your business or career." That's speaking in the language of your association staff culture. If you want a member to care about your services (i.e., look forward to receiving your newsletters and attending your conferences), you have to define and deliver value through them in the language they understand.

And that requires learning the language of your member, not teaching them to speak yours. How would a member describe a great educational experience? Or information of direct relevance to their business? Specifically, what information are they looking for? Concretely, what do they do with that information once they find it? And measurably, what effect does the application of that information have on their business or career?

Only after you've learned to communicate your association offerings in these terms, in the language spoken by your members when they are not interacting with your association, will you find the success you're most likely looking for.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

https://www.spiabroad.com/5-creative-ways-to-use-pinterest-for-learning-a-foreign-language/

BLOG TOPICS

▼

Monday, May 30, 2016

Saturday, May 28, 2016

Independence Day by Richard Ford

I have a theory. A good novel will tell you what it’s about in its opening pages. Not who the characters are or what’s going to happen in its plot, but what it’s about.

A sad fact, of course, about adult life is that you see the very things you’ll never adapt to coming toward you on the horizon. You see them as the problems they are, you worry like hell about them, you make provisions, take precautions, fashion adjustments; you tell yourself you’ll have to change your way of doing things. Only you don’t. You can’t. Somehow it’s already too late. And maybe it’s even worse than that: maybe the thing you see coming from far away is not the real thing, the thing that scares you, but its aftermath. And what you’ve feared will happen has already taken place. This is similar in spirit to the realization that all the great new advances of medical science will have no benefit for us at all, though we cheer them on, hope a vaccine might be ready in time, think things could still get better. Only it’s too late there too. And in that very way our life gets over before we know it. We miss it. And like the poet said: “The ways we miss our lives are life.”

This is on page 5 of Richard Ford’s Independence Day, and I flagged it as soon as I read it. This painful reality of “adult” life, that no matter what, it’s already too late to fix anything, is absolutely the central theme of the novel.

And it’s typified by the experiences of our first person narrator, Frank Bascombe, a former sportswriter and now a real estate agent, a former husband, now with an ex-wife, a teenage son, and a middle-aged girlfriend. Independence Day paints an odd time in Frank’s life, something he himself calls his Existence Period, a time with no past and no future, where anything can happen but isn’t likely to.

But on any day I can rise and go about all my normal duties in a normal way; or I could drive down to Trenton, pull off a convenience-store stickup or a contract hit, then fly off to Caribou, Alberta, walk off naked into the muskeg and no one would notice much of anything out of the ordinary about my life, or even register I was gone. It could take days, possibly weeks, for serious personal dust to be raised. (It’s not exactly as if I didn’t exist, but that I don’t exist as much.) So, if I didn’t appear tomorrow to get my son, or if I showed up with Sally as a provocative late sign-up to my team, if I showed up with the fat lady from the circus or a box of spitting cobras, as little as possible would be made of it by all concerned, partly in order that everybody retain as much of their own personal freedom and flexibility as possible, and partly because I just wouldn’t be noticed that much per se. (This reflects my own wishes, of course--the unhurried nature of my single life in the grip of the Existence Period--though it may also imply that laissez-faire is not precisely the same as independence.)

This provides the double meaning of the title (another probable pre-requisite of any good novel). The plot involves Frank’s preparation for and participation in an extended Independence Day weekend trip with his son, but it’s also an ironical comment on the nature of Frank’s independence. Despite the apparent capability of doing anything, he is so benumbed by the structures and conventions of his adult life that he is incapable of mustering the energy to do much more than go through the motions. If his life can take him so drastically from place to place, especially in a manner unforeseen and undesired, it’s better not to hope or actively engage in the business of living.

Frank has plenty of fears. There are fears about his son, who is beginning to manifest some antisocial behaviors.

And who could help wondering: is my surviving son already out of reach and crazy as a betsy bug, or headed fast in that dire direction? Are his problems the product of haywire neurotransmitters, only solvable by preemptive chemicals? … Will he turn gradually into a sly recluse with a bad complexion, rotten teeth, bitten nails, yellow eyes, who abandons school early, hits the road, falls in with the wrong bunch, tries drugs, and finally becomes convinced trouble is his only dependable friend, until one sunny Saturday it, too, betrays him in some unthought-of and unbearable way, after which he stops off at a suburban gun store, then spirits on to some quilty mayhem in a public place? (This I frankly don’t expect, since he has yet to exhibit any of the “big three” of childhood homicidal dementia: attraction to fire, the need to torture helpless animals, or bedwetting; and because he is in fact quite softhearted and mirthful, and always has been.) Or, and in the best-case scenario, is he--as happens to us all and as his mother hopes--merely going through a phase, so that in eight weeks he’ll be trying out for lonely end on the Deep River JV.

God only knows, right? Really knows?

This passage sets a common precedent for much of the inner dialogue of the novel. Question, question, question, softened by a dose of reality, and then dismissed with a set of hands thrown up at the end. Is he a monster? Probably not. But who can tell?

There are fears about the intentions of others.

The truth is, however, we know little and can find out precious little more about others, even though we stand in their presence, hear their complaints, ride the roller coaster with them, sell them houses, consider the happiness of their children--only in a flash or a gasp or the slam of a car door to see them disappear and be gone forever. Perfect strangers.

This (cleverly, I think) comes after forty or more pages of exposition on two of Frank’s real estate clients--Joe and Phyllis Markham. So many pages so early in the novel, in fact, that I was beginning to think that the novel was going to be about the Markhams (it isn’t). Having Frank call them perfect strangers after telling us so much about them helps shake the foundation we think he is building, and gives us deeper insight into the rules that govern his Existence Period.

And there are fears about his own death, as likely as not, in squalor and obscurity--either like Clair, a younger real estate agent Frank had a brief fling with, murdered in a seeming random event while showing properties; or like an unknown father staying at the same motel as Frank, his room broken into and killed for his valuables.

And as I lie in bed here, still alive myself, the Fedders blowing brisk, chemically cooled breezes across my sheets, I try to find solace against the way this memory and the night’s events make me feel, which is: bracketed, limbo’d, unable to budge, as illustrated amply by Mr. Tanks and me standing side by side in the murderous night, unable to strike a spark, utter a convincingly encouraging word to the other, be of assistance, shout halloo, dip a wing; unable at the sad passage of another human to the barren beyond to share a hope for the future. Whereas, had we but been able, our spirits might’ve lightened.

Death, veteran of death that I am, seems so near now, so plentiful, so oh-so-drastic and significant, that it scares me witless. Though in a few hours I’ll embark with my son upon the other tack, the hopeful, life-affirming, anti-nullity one, armed only with words and myself to build a case, and nothing half as dramatic and persuasive as a black body bag, or lost memories of lost love.

Suddenly my heart again goes bangety-bang, bangety-bangety-bang, as if I myself were about to exit life in a hurry. And if I could, I would spring up, switch on the light, dial someone and shout right down into the hard little receiver, “It’s okay. I got away. It was goddamned close, I’ll tell ya. It didn’t get me, thought. I smelled its breath, saw its red eyes in the dark, shining. A clammy hand touched mine. But I made it. I survived. Wait for me. Wait for me. Not that much is left to do.” Only there’s no one. No one here or anywhere near to say any of this to. And I’m sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry.

But none of these fears--as pressing and as sublimely expressed as Ford offers them--cause Frank to act. Because that’s not what this novel is about. Near the end of the novel, while at the Baseball Hall of Fame with his son, Frank bumps into his own step-brother, Irv, the product of a union between Frank’s mother and her second husband, someone Frank hasn’t seen in years. Irv shows Frank a photograph he continues to carry around.

“It’s us, Frank,” Irv says, and looks at me amazed. “It’s you and Jake and your mom and me, in Skokie, in 1963. You can see how pretty your mom is, though she looks thin already. We’re all there on the porch. Do you even remember it?” Irv stares at me, damp-lipped and happy behind his glasses, holding his precious artifact out for me to see once more.

“I guess I don’t.” I look again reluctantly at this little pinch-hole window to my long-gone past, feel a quickening torque of heart pain--unexceptional, nothing like Irv’s catch of dread--and once again proffer it back. I’m a man who wouldn’t recognize his own mother. Possibly I should be in politics.

“Me either really.” Irv looks appreciatively down at himself for the eight jillionth time, trying to leech some wafting synchronicity out of his image, then shakes his head and re-snugs it among his other wallet votives and crams it all back into his pocket, where it belongs.

It’s more of the same. Almost 400 pages in, and Frank is still not acting, still not recognizing his own past, still not envisioning his own future. And for those of us like Irv, actively trying to connect the gossamer threads of our own lives together into some kind of coherent narrative, being confronted by such ennui and inaction, we can’t help but feel embarrassed, as if we secretly fear Frank has figured something out that has eluded us.

But, of course, he hasn’t. My theory about novels has a second part to it. A good novel tells you in its opening pages what it’s about. And a great novel sums up that theme in its closing pages in a way that isn’t forced or clumsy. That’s a real challenge for Ford in Independence Day, since it is essentially a novel about existing, about not reacting, about never taking risks.

The best “summing up” comes a few pages before the end, when Frank is watching parachuters in an air show on the titular Independence Day.

I climb out of my car onto the grass and stare at the sky to glimpse the plane the jumpers have leaped free of, some little muttering dot on the infinite. As always, this is what interests me: the jump, of course, but the hazardous place jumped from even more; the old safety, the ordinary and predictable, which makes a swan dive into invisible empty air seem perfect, lovely, the one thing that’ll do. This provokes butterflies, ignites danger.

Needless to say, I would never consider it, even if I packed my own gear with a sapper’s precision, made friends I could die with, serviced the plane with my own lubricants, turned the prop, piloted the crate to the very spot in space, and even uttered the words they all must utter at least silently as they go--right? “Life’s too short” (or long). “I have nothing to lose but my fears” (wrong). “What’s anything worth if you won’t risk pissing it away?” (Taken together, I’m sure it’s what “Geronimo” means in Apache.) I, though, would always find a reason not to risk it; since for me, the wire, the plane, the platform, the bridge, the trestle, the window ledge--these would preoccupy me, flatter my nerve with their own prosy hazards, greater even than the risk of brilliantly daring death. I’m no hero, as my wife suggested years ago.

This is Frank Bascombe--and perhaps this is also Richard Ford, and the writer than lives within. Neither nostalgic for the past nor dreaming of the future, but always preoccupied with the everlasting present, the place few others pay any attention to.

Inside the Craft

As earlier mentioned, Frank Bascombe was a sportswriter (the Sportswriter in a previous Ford novel), so when he starts talking about what he misses about the craft, my ears really perk up, listening carefully for Ford’s own voice instead of Frank’s.

Sometimes, though not that often, I wish I were still a writer, since so much goes through anybody’s mind and right out the window, whereas, for a writer--even a shitty writer--so much less is lost. If you get divorced from your wife, for instance, and later think back to a time, say, twelve years before, when you almost broke up the first time but didn't because you decided you loved each other too much or were too smart, or because you both had gumption and a shred of good character, then later after everything was finished, you decided you actually should’ve gotten divorced long before because you think now you missed something wonderful and irreplaceable and as a result are filled with whistling longing you can’t seem to shake--if you were a writer, even a half-baked short-story writer, you’d have someplace to put that fact buildup so you wouldn’t have to think about it all the time. You’d just write it all down, put quotes around the most gruesome and rueful lines, stick them in somebody’s mouth who doesn’t exist (or better, a thinly disguised enemy of yours), turn it into pathos and get it all off your ledger for the enjoyment of others.

Writers don’t actually do that, do they?

And should someone actually recognize themselves in these half-baked short-stories? Recognize and resent the gruesome and rueful lines you have put in their mouth? The way Frank’s ex-wife Ann does in Independence Day?

Indeed, I often tried telling her that her contribution was not to be a character but to make my little efforts at creation urgent by being so wonderful that I loved her; stories being after all just words giving varied form to larger, compelling but otherwise speechless mysteries such as love and passion. In that way, I explained, she was my muse; muses being not comely, playful feminine elves who sit on your shoulder suggesting better word choices and tittering when you get one right, but powerful life-and-death forces that threaten to suck you right out the bottom of your boat unless you can heave enough crates and boxes--words, in a writer’s case--into the breach.

Serious business, this writing of half-baked stories. In them, writers grapple with forces capable of destroying them.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

A sad fact, of course, about adult life is that you see the very things you’ll never adapt to coming toward you on the horizon. You see them as the problems they are, you worry like hell about them, you make provisions, take precautions, fashion adjustments; you tell yourself you’ll have to change your way of doing things. Only you don’t. You can’t. Somehow it’s already too late. And maybe it’s even worse than that: maybe the thing you see coming from far away is not the real thing, the thing that scares you, but its aftermath. And what you’ve feared will happen has already taken place. This is similar in spirit to the realization that all the great new advances of medical science will have no benefit for us at all, though we cheer them on, hope a vaccine might be ready in time, think things could still get better. Only it’s too late there too. And in that very way our life gets over before we know it. We miss it. And like the poet said: “The ways we miss our lives are life.”

This is on page 5 of Richard Ford’s Independence Day, and I flagged it as soon as I read it. This painful reality of “adult” life, that no matter what, it’s already too late to fix anything, is absolutely the central theme of the novel.

And it’s typified by the experiences of our first person narrator, Frank Bascombe, a former sportswriter and now a real estate agent, a former husband, now with an ex-wife, a teenage son, and a middle-aged girlfriend. Independence Day paints an odd time in Frank’s life, something he himself calls his Existence Period, a time with no past and no future, where anything can happen but isn’t likely to.

But on any day I can rise and go about all my normal duties in a normal way; or I could drive down to Trenton, pull off a convenience-store stickup or a contract hit, then fly off to Caribou, Alberta, walk off naked into the muskeg and no one would notice much of anything out of the ordinary about my life, or even register I was gone. It could take days, possibly weeks, for serious personal dust to be raised. (It’s not exactly as if I didn’t exist, but that I don’t exist as much.) So, if I didn’t appear tomorrow to get my son, or if I showed up with Sally as a provocative late sign-up to my team, if I showed up with the fat lady from the circus or a box of spitting cobras, as little as possible would be made of it by all concerned, partly in order that everybody retain as much of their own personal freedom and flexibility as possible, and partly because I just wouldn’t be noticed that much per se. (This reflects my own wishes, of course--the unhurried nature of my single life in the grip of the Existence Period--though it may also imply that laissez-faire is not precisely the same as independence.)

This provides the double meaning of the title (another probable pre-requisite of any good novel). The plot involves Frank’s preparation for and participation in an extended Independence Day weekend trip with his son, but it’s also an ironical comment on the nature of Frank’s independence. Despite the apparent capability of doing anything, he is so benumbed by the structures and conventions of his adult life that he is incapable of mustering the energy to do much more than go through the motions. If his life can take him so drastically from place to place, especially in a manner unforeseen and undesired, it’s better not to hope or actively engage in the business of living.

Frank has plenty of fears. There are fears about his son, who is beginning to manifest some antisocial behaviors.

And who could help wondering: is my surviving son already out of reach and crazy as a betsy bug, or headed fast in that dire direction? Are his problems the product of haywire neurotransmitters, only solvable by preemptive chemicals? … Will he turn gradually into a sly recluse with a bad complexion, rotten teeth, bitten nails, yellow eyes, who abandons school early, hits the road, falls in with the wrong bunch, tries drugs, and finally becomes convinced trouble is his only dependable friend, until one sunny Saturday it, too, betrays him in some unthought-of and unbearable way, after which he stops off at a suburban gun store, then spirits on to some quilty mayhem in a public place? (This I frankly don’t expect, since he has yet to exhibit any of the “big three” of childhood homicidal dementia: attraction to fire, the need to torture helpless animals, or bedwetting; and because he is in fact quite softhearted and mirthful, and always has been.) Or, and in the best-case scenario, is he--as happens to us all and as his mother hopes--merely going through a phase, so that in eight weeks he’ll be trying out for lonely end on the Deep River JV.

God only knows, right? Really knows?

This passage sets a common precedent for much of the inner dialogue of the novel. Question, question, question, softened by a dose of reality, and then dismissed with a set of hands thrown up at the end. Is he a monster? Probably not. But who can tell?

There are fears about the intentions of others.

The truth is, however, we know little and can find out precious little more about others, even though we stand in their presence, hear their complaints, ride the roller coaster with them, sell them houses, consider the happiness of their children--only in a flash or a gasp or the slam of a car door to see them disappear and be gone forever. Perfect strangers.

This (cleverly, I think) comes after forty or more pages of exposition on two of Frank’s real estate clients--Joe and Phyllis Markham. So many pages so early in the novel, in fact, that I was beginning to think that the novel was going to be about the Markhams (it isn’t). Having Frank call them perfect strangers after telling us so much about them helps shake the foundation we think he is building, and gives us deeper insight into the rules that govern his Existence Period.

And there are fears about his own death, as likely as not, in squalor and obscurity--either like Clair, a younger real estate agent Frank had a brief fling with, murdered in a seeming random event while showing properties; or like an unknown father staying at the same motel as Frank, his room broken into and killed for his valuables.

And as I lie in bed here, still alive myself, the Fedders blowing brisk, chemically cooled breezes across my sheets, I try to find solace against the way this memory and the night’s events make me feel, which is: bracketed, limbo’d, unable to budge, as illustrated amply by Mr. Tanks and me standing side by side in the murderous night, unable to strike a spark, utter a convincingly encouraging word to the other, be of assistance, shout halloo, dip a wing; unable at the sad passage of another human to the barren beyond to share a hope for the future. Whereas, had we but been able, our spirits might’ve lightened.

Death, veteran of death that I am, seems so near now, so plentiful, so oh-so-drastic and significant, that it scares me witless. Though in a few hours I’ll embark with my son upon the other tack, the hopeful, life-affirming, anti-nullity one, armed only with words and myself to build a case, and nothing half as dramatic and persuasive as a black body bag, or lost memories of lost love.

Suddenly my heart again goes bangety-bang, bangety-bangety-bang, as if I myself were about to exit life in a hurry. And if I could, I would spring up, switch on the light, dial someone and shout right down into the hard little receiver, “It’s okay. I got away. It was goddamned close, I’ll tell ya. It didn’t get me, thought. I smelled its breath, saw its red eyes in the dark, shining. A clammy hand touched mine. But I made it. I survived. Wait for me. Wait for me. Not that much is left to do.” Only there’s no one. No one here or anywhere near to say any of this to. And I’m sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry.

But none of these fears--as pressing and as sublimely expressed as Ford offers them--cause Frank to act. Because that’s not what this novel is about. Near the end of the novel, while at the Baseball Hall of Fame with his son, Frank bumps into his own step-brother, Irv, the product of a union between Frank’s mother and her second husband, someone Frank hasn’t seen in years. Irv shows Frank a photograph he continues to carry around.

“It’s us, Frank,” Irv says, and looks at me amazed. “It’s you and Jake and your mom and me, in Skokie, in 1963. You can see how pretty your mom is, though she looks thin already. We’re all there on the porch. Do you even remember it?” Irv stares at me, damp-lipped and happy behind his glasses, holding his precious artifact out for me to see once more.

“I guess I don’t.” I look again reluctantly at this little pinch-hole window to my long-gone past, feel a quickening torque of heart pain--unexceptional, nothing like Irv’s catch of dread--and once again proffer it back. I’m a man who wouldn’t recognize his own mother. Possibly I should be in politics.

“Me either really.” Irv looks appreciatively down at himself for the eight jillionth time, trying to leech some wafting synchronicity out of his image, then shakes his head and re-snugs it among his other wallet votives and crams it all back into his pocket, where it belongs.

It’s more of the same. Almost 400 pages in, and Frank is still not acting, still not recognizing his own past, still not envisioning his own future. And for those of us like Irv, actively trying to connect the gossamer threads of our own lives together into some kind of coherent narrative, being confronted by such ennui and inaction, we can’t help but feel embarrassed, as if we secretly fear Frank has figured something out that has eluded us.

But, of course, he hasn’t. My theory about novels has a second part to it. A good novel tells you in its opening pages what it’s about. And a great novel sums up that theme in its closing pages in a way that isn’t forced or clumsy. That’s a real challenge for Ford in Independence Day, since it is essentially a novel about existing, about not reacting, about never taking risks.

The best “summing up” comes a few pages before the end, when Frank is watching parachuters in an air show on the titular Independence Day.

I climb out of my car onto the grass and stare at the sky to glimpse the plane the jumpers have leaped free of, some little muttering dot on the infinite. As always, this is what interests me: the jump, of course, but the hazardous place jumped from even more; the old safety, the ordinary and predictable, which makes a swan dive into invisible empty air seem perfect, lovely, the one thing that’ll do. This provokes butterflies, ignites danger.

Needless to say, I would never consider it, even if I packed my own gear with a sapper’s precision, made friends I could die with, serviced the plane with my own lubricants, turned the prop, piloted the crate to the very spot in space, and even uttered the words they all must utter at least silently as they go--right? “Life’s too short” (or long). “I have nothing to lose but my fears” (wrong). “What’s anything worth if you won’t risk pissing it away?” (Taken together, I’m sure it’s what “Geronimo” means in Apache.) I, though, would always find a reason not to risk it; since for me, the wire, the plane, the platform, the bridge, the trestle, the window ledge--these would preoccupy me, flatter my nerve with their own prosy hazards, greater even than the risk of brilliantly daring death. I’m no hero, as my wife suggested years ago.

This is Frank Bascombe--and perhaps this is also Richard Ford, and the writer than lives within. Neither nostalgic for the past nor dreaming of the future, but always preoccupied with the everlasting present, the place few others pay any attention to.

Inside the Craft

As earlier mentioned, Frank Bascombe was a sportswriter (the Sportswriter in a previous Ford novel), so when he starts talking about what he misses about the craft, my ears really perk up, listening carefully for Ford’s own voice instead of Frank’s.

Sometimes, though not that often, I wish I were still a writer, since so much goes through anybody’s mind and right out the window, whereas, for a writer--even a shitty writer--so much less is lost. If you get divorced from your wife, for instance, and later think back to a time, say, twelve years before, when you almost broke up the first time but didn't because you decided you loved each other too much or were too smart, or because you both had gumption and a shred of good character, then later after everything was finished, you decided you actually should’ve gotten divorced long before because you think now you missed something wonderful and irreplaceable and as a result are filled with whistling longing you can’t seem to shake--if you were a writer, even a half-baked short-story writer, you’d have someplace to put that fact buildup so you wouldn’t have to think about it all the time. You’d just write it all down, put quotes around the most gruesome and rueful lines, stick them in somebody’s mouth who doesn’t exist (or better, a thinly disguised enemy of yours), turn it into pathos and get it all off your ledger for the enjoyment of others.

Writers don’t actually do that, do they?

And should someone actually recognize themselves in these half-baked short-stories? Recognize and resent the gruesome and rueful lines you have put in their mouth? The way Frank’s ex-wife Ann does in Independence Day?

Indeed, I often tried telling her that her contribution was not to be a character but to make my little efforts at creation urgent by being so wonderful that I loved her; stories being after all just words giving varied form to larger, compelling but otherwise speechless mysteries such as love and passion. In that way, I explained, she was my muse; muses being not comely, playful feminine elves who sit on your shoulder suggesting better word choices and tittering when you get one right, but powerful life-and-death forces that threaten to suck you right out the bottom of your boat unless you can heave enough crates and boxes--words, in a writer’s case--into the breach.

Serious business, this writing of half-baked stories. In them, writers grapple with forces capable of destroying them.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Monday, May 23, 2016

The Truly Honest Attrition Clause

My first job in association management was the meeting planner. That was in 1992. As my career progressed, there came a day when I was no longer "the" meeting planner. But even in those higher level positions, including my chief staff executive role today, it's always been my signature that goes on the bottom line of the hotel contract.

And over all those years and those untold number of contracts, I've yet to come across the truly honest attrition clause.

Attrition, in case you're not familiar with the term, is what hotels call the fee you are required to pay in the event the sleeping rooms you contracted for your meeting or convention don't get used by your attendees.

The clauses in hotel contracts that describe them are usually full of convoluted language, focused mostly on how much the hotel will be harmed if the association doesn’t fill its block. They mostly are, in my experience, dishonest in the sense that they force the association to agree to things that aren't true (like it's difficult for a hotel to calculate lost profit) and to promise to do things it typically can't (like force its members to book rooms in the hotel, and cover the cost of those rooms if they don't).

So what do I mean by a truly honest attrition clause? Well, it might look something like this:

Hotel and Group acknowledge that they both have the same objective. Namely, both parties want a full block of happy conference attendees, spending money in the Hotel's outlets and utilizing the Hotel's services. As such, both parties agree to work together in good faith, sharing information and identifying mutually-beneficial strategies designed to achieve that goal.

Both parties also acknowledge that Group is an association, with no binding authority to compel its members to attend its conference, or to book rooms at the Hotel. Both parties have therefore reviewed Group's history of rooms utilized and pace of reservations at previous conferences, assessed market forces that may impact the decisions of the Group's members to attend the conference, and hereby mutually agree that the contracted room block represents the best possible estimate of rooms expected to be utilized by Group's members.

Despite these mutual agreements and understandings, both parties also acknowledge that fewer rooms than anticipated may be used by the Group's members. This risk of this occurence represents a potential loss of anticipated revenue to Hotel, a situation neither party expects nor desires. To protect against this unfortunate situation, both parties agree to mutually review weekly pickup reports. Should reservations fall behind the Group's historical pace, Hotel is allowed to remove an appropriate percentage of rooms from Group's block and sell them to other parties at rates of their choosing. Should reservations exceed the Group's historical pace, Hotel will add an appropriate percentage of rooms to the Group's block and offer them to Group's members at the group rate. There is no cut-off for this activity.

I've been reading hotel contracts for twenty-four years, and I've never seen anything like this. It's honest because it first recognizes the partnership that must exist between a hotel and an association for a successful conference, and then provides a mechanism for both parties to achieve a positive outcome for themselves.

And although it wasn't my intention when I set out to write it, I realize now that the best part of this attrition clause is that the word attrition does not appear in it.

Who's with me?

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://www.onemag.org/attrition.htm

And over all those years and those untold number of contracts, I've yet to come across the truly honest attrition clause.

Attrition, in case you're not familiar with the term, is what hotels call the fee you are required to pay in the event the sleeping rooms you contracted for your meeting or convention don't get used by your attendees.

The clauses in hotel contracts that describe them are usually full of convoluted language, focused mostly on how much the hotel will be harmed if the association doesn’t fill its block. They mostly are, in my experience, dishonest in the sense that they force the association to agree to things that aren't true (like it's difficult for a hotel to calculate lost profit) and to promise to do things it typically can't (like force its members to book rooms in the hotel, and cover the cost of those rooms if they don't).

So what do I mean by a truly honest attrition clause? Well, it might look something like this:

Hotel and Group acknowledge that they both have the same objective. Namely, both parties want a full block of happy conference attendees, spending money in the Hotel's outlets and utilizing the Hotel's services. As such, both parties agree to work together in good faith, sharing information and identifying mutually-beneficial strategies designed to achieve that goal.

Both parties also acknowledge that Group is an association, with no binding authority to compel its members to attend its conference, or to book rooms at the Hotel. Both parties have therefore reviewed Group's history of rooms utilized and pace of reservations at previous conferences, assessed market forces that may impact the decisions of the Group's members to attend the conference, and hereby mutually agree that the contracted room block represents the best possible estimate of rooms expected to be utilized by Group's members.

Despite these mutual agreements and understandings, both parties also acknowledge that fewer rooms than anticipated may be used by the Group's members. This risk of this occurence represents a potential loss of anticipated revenue to Hotel, a situation neither party expects nor desires. To protect against this unfortunate situation, both parties agree to mutually review weekly pickup reports. Should reservations fall behind the Group's historical pace, Hotel is allowed to remove an appropriate percentage of rooms from Group's block and sell them to other parties at rates of their choosing. Should reservations exceed the Group's historical pace, Hotel will add an appropriate percentage of rooms to the Group's block and offer them to Group's members at the group rate. There is no cut-off for this activity.

I've been reading hotel contracts for twenty-four years, and I've never seen anything like this. It's honest because it first recognizes the partnership that must exist between a hotel and an association for a successful conference, and then provides a mechanism for both parties to achieve a positive outcome for themselves.

And although it wasn't my intention when I set out to write it, I realize now that the best part of this attrition clause is that the word attrition does not appear in it.

Who's with me?

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://www.onemag.org/attrition.htm

Monday, May 16, 2016

Associations Are Non-Profits for a Reason

There is a clear and important reason that associations are organized as non-profit organizations, and it isn't so they can get out of paying taxes.

My musings in this regard were inspired by this post by Anna Caraveli on The Demand Networks blog. Titled, Are you Marching to your Board’s or your Customers’ Pace?, the post explores the difficult and important territory of slow-moving associations growing increasingly obsolete, either because they disenfranchise younger members or because they lose the service delivery battle with for-profit competitors (or both).

Caraveli, always a vocal champion for associations to adopt a "for-profit" mindset in identifying and responding to the needs of their members, reveals in this post a growing frustration with the opposite point of view, still well entrenched in many areas of the association landscape. Associations, the countervailing wisdom goes, are not organized as for-profit entities for a reason. Their strengths are not tied to agility and market responsiveness, but to stability and advocacy, and as such, they have cultures and governance structures that resist (and should resist, I suppose) the kind of market-driven solutions Caraveli supports. Caraveli, to the people that hold this viewpoint, comes across as not fundamentally understanding the role of associations in our environment. While to Caraveli, these defenders of the status quo are just whistling past their own graveyards.

It's a good post. Don't just accept my paraphrasing and, with apologies to Caraveli, my unasked-for analysis. Go read it for yourself.

If nothing else, it got me thinking. Thinking specifically about what it uniquely means to be an association and whether that has any lasting utility in the marketplace. Because, truth be told, my gut is more on the side of those that Caraveli is railing against. Although I loathe to think of myself as a "defender of the status quo," I have to admit that I have more allegiance to the idea that associations are not solely here to provide market-driven goods and services to their members. Too much focus in that area, in fact, robs an association of its ability to pursue its vital purpose.

Clearly, I'm talking about mission, the socially-beneficial reason that every association exists and was granted their non-profit status in the first place. And while I very much ascribe to common maxim of "No Money, No Mission," too much focus on money for money's sake can result in no one paying attention to the mission at all.

Here's how I look at it. Every association, to be successful, must master two distinct types of relationships with its members. First comes the transactional. As a member of this association you get the following benefits, and those benefits have bottom-line value in your marketplace. You get intelligence you can parlay into better operating ratios, or education that you can parlay into personal career growth and advancement. When it comes to the transactional relationship, Caraveli and her demand-driven approach has a lot to offer struggling associations. You'd better figure out what your members need and position your association as the only place they can get it. If you don't get this right, for-profit competitors are going to put you out of business quick.

But there is a second kind of relationship that associations must have with their memberships, a relationship I call aspirational. This almost always coincides with the non-profit mission of the organization. Our association is dedicated to solving a specific challenge or problem that our industry or profession is facing. It's not something any of our members can do by themselves. In fact, it can only be tackled through the collective actions of everyone in the industry or profession, and our association is the instrument that allows that collective action to be legal and focused. When it comes to the aspirational relationship, the cultures and governance structures of Caraveli's "defenders of the status quo" have the most to offer. They are what give associations the authority and support they need to tackle its aspirational challenges.

Inside an association, the need to maintain both of these relationships can create an enormous amount of tension. Unless everyone understands that there are two objectives here, and that the objectives must live in harmony with one another, things inevitably decay into warring factions. When the transactional side wins, the association loses its way, and becomes a mere provider of services, and often one still less nimble and effective than for-profit competitors. When the aspirational side wins, the association loses its members, who, as altruistic as they may be, have businesses to run and careers to grow, and will not support any organization that doesn't help them with these goals.

As I said at the beginning, there is a clear and important reason that associations are organized as non-profit organizations. It is to fulfill their socially-beneficial missions. But just because you can't fulfill that mission without providing your members with valuable responses to their market-driven needs, don't let the quest to provide those responses destroy your ability to fulfill your mission.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://theconnectedcause.com/quick-review-nonprofit-applications-salesforce-causeview/

My musings in this regard were inspired by this post by Anna Caraveli on The Demand Networks blog. Titled, Are you Marching to your Board’s or your Customers’ Pace?, the post explores the difficult and important territory of slow-moving associations growing increasingly obsolete, either because they disenfranchise younger members or because they lose the service delivery battle with for-profit competitors (or both).

Caraveli, always a vocal champion for associations to adopt a "for-profit" mindset in identifying and responding to the needs of their members, reveals in this post a growing frustration with the opposite point of view, still well entrenched in many areas of the association landscape. Associations, the countervailing wisdom goes, are not organized as for-profit entities for a reason. Their strengths are not tied to agility and market responsiveness, but to stability and advocacy, and as such, they have cultures and governance structures that resist (and should resist, I suppose) the kind of market-driven solutions Caraveli supports. Caraveli, to the people that hold this viewpoint, comes across as not fundamentally understanding the role of associations in our environment. While to Caraveli, these defenders of the status quo are just whistling past their own graveyards.

It's a good post. Don't just accept my paraphrasing and, with apologies to Caraveli, my unasked-for analysis. Go read it for yourself.

If nothing else, it got me thinking. Thinking specifically about what it uniquely means to be an association and whether that has any lasting utility in the marketplace. Because, truth be told, my gut is more on the side of those that Caraveli is railing against. Although I loathe to think of myself as a "defender of the status quo," I have to admit that I have more allegiance to the idea that associations are not solely here to provide market-driven goods and services to their members. Too much focus in that area, in fact, robs an association of its ability to pursue its vital purpose.

Clearly, I'm talking about mission, the socially-beneficial reason that every association exists and was granted their non-profit status in the first place. And while I very much ascribe to common maxim of "No Money, No Mission," too much focus on money for money's sake can result in no one paying attention to the mission at all.

Here's how I look at it. Every association, to be successful, must master two distinct types of relationships with its members. First comes the transactional. As a member of this association you get the following benefits, and those benefits have bottom-line value in your marketplace. You get intelligence you can parlay into better operating ratios, or education that you can parlay into personal career growth and advancement. When it comes to the transactional relationship, Caraveli and her demand-driven approach has a lot to offer struggling associations. You'd better figure out what your members need and position your association as the only place they can get it. If you don't get this right, for-profit competitors are going to put you out of business quick.

But there is a second kind of relationship that associations must have with their memberships, a relationship I call aspirational. This almost always coincides with the non-profit mission of the organization. Our association is dedicated to solving a specific challenge or problem that our industry or profession is facing. It's not something any of our members can do by themselves. In fact, it can only be tackled through the collective actions of everyone in the industry or profession, and our association is the instrument that allows that collective action to be legal and focused. When it comes to the aspirational relationship, the cultures and governance structures of Caraveli's "defenders of the status quo" have the most to offer. They are what give associations the authority and support they need to tackle its aspirational challenges.

Inside an association, the need to maintain both of these relationships can create an enormous amount of tension. Unless everyone understands that there are two objectives here, and that the objectives must live in harmony with one another, things inevitably decay into warring factions. When the transactional side wins, the association loses its way, and becomes a mere provider of services, and often one still less nimble and effective than for-profit competitors. When the aspirational side wins, the association loses its members, who, as altruistic as they may be, have businesses to run and careers to grow, and will not support any organization that doesn't help them with these goals.

As I said at the beginning, there is a clear and important reason that associations are organized as non-profit organizations. It is to fulfill their socially-beneficial missions. But just because you can't fulfill that mission without providing your members with valuable responses to their market-driven needs, don't let the quest to provide those responses destroy your ability to fulfill your mission.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://theconnectedcause.com/quick-review-nonprofit-applications-salesforce-causeview/

Saturday, May 14, 2016

Colonel Roosevelt by Edmund Morris

In 1910, after Theodore Roosevelt finished his second term as president of the United States, he went on a world-wide tour, where he was seen by all the heads of state in Europe and hailed as the most famous man in the world. That’s where this, Edmund Morris’s third of three volumes of biography, begins.

Surrounded by flunkeys, guarded wherever he went, Roosevelt was screened off from the extraordinary changes occurring at lower levels of Viennese society--changes more radical than anywhere else in Europe, and coincident with Austria-Hungary’s thrust into the Balkans. He did not see the pornographic nudes of Klimt and Schiele, Kokoschka’s explosive studies of angst-filled burghers, the rectilinear architecture of the Secessionists. He was deaf to the atonality of Schonberg and the warnings of local poets and playwrights that an apocalypse was coming.

And in this paragraph, I discovered another one of those PhD theses I would have written in another life. Does the content and style of progressive art in one era accurately predict the historical events and conflicts of the next?

It’s an interesting question--made all the more interesting when, 200 pages and three years later, after losing his bid for an unprecedented third term as president, and on his rival Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration day, Roosevelt finally gets a glimpse of some of that progressive art (decidedly American, not European) at a “Futurists Exhibition” at the Sixty-ninth Regiment Armory in midtown Manhattan.

Here’s how Edmund Morris, as graceful a writer as you’re ever likely to meet, conveys the scene and Roosevelt’s reaction to it all.

Moving on through five more galleries of contemporary American art, Roosevelt saw nothing by Saint-Gaudens, Frederick MacMonnies, William Merritt Chase, and other favorites of his presidency. He did not miss them. They had had too long a reign, with their effete laurel wreaths and Grecian profiles. It was clear that the show’s organizers, headed by the symbolist painter Arthur B. Davies, intended to eradicate the beaux arts style from the national memory. Even Sargent was shunned, in favor of young American artists of powerful, if not yet radical originality: George Bellows, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, and dozens of women willing to portray their sex without prettification.

This is art history as well as biography, Morris in this one paragraph and the few that follow easily capturing the essence of the changes coming to American society in the early 20th century. And Roosevelt?

Roosevelt was taken with Ethel Myers’s plastilene group “Fifth Avenue Gossips,”

whose perambulatory togetherness reminded him of the fifteenth idyll of Theocritus. He liked the social realism of John Sloan’s “Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair”

and George Luks’s camera quick sketches of animal activity at the Bronx Zoo.

Leon Kroll’s “Terminal Yards” impressed him,

although it represented the kind of desecration of the Hudson Palisades that he and George Perkins had worked to curtail. From a vertiginous, snowcapped height, the artist’s eagle eye looked down on railroad sidings and heaps of slag. Drifting vapor softened the ugliness and made it mysteriously poetic.

Note that, like all of us, Roosevelt is only able to experience art through the prism of his own philosophical and political sensibilities. Read on.

What pleased Roosevelt about the work of these “Ashcan” painters, and indeed the entire American showing as he wandered on, was the lack of “simpering, self-satisfied conventionality.” All his life he had deplored the deference his countrymen tended to extend toward the art and aristocracy of the Old World. Sloan was a social realist as unsentimental as Daumier, but bigger of heart. Walt Kuhn’s joyful “Morning”

had the explosive energy of a Van Gogh landscape, minus the neurosis. Hartley’s foreflattened “Still Life No. 1”

was the work of a stateside Cezanne, its Indian rug and tapestries projecting a geometry unseen in Provence.

Roosevelt responded to what he saw as American art, unsaddled from the conventions of Europe and its artistic schools. And yet…

His enjoyment did not diminish when he found himself among the works of European moderns loosely catalogued as “post-impressionist.” He was blind to a piece of pure abstraction by Wassily Kandinsky, but responded happily to the dreamy fantasies of Odilon Redon and the virtuoso draftsmanship of Augustus John, as well as to Whistler, Monet, Cezanne, and other acknowledged revolutionaries.

For this was Roosevelt, too. Welcomed in the salons of the European capitals, enjoying their luxuries and their deep historical weight, but always wistful, even when there, for the open American horizon--what he sought to tame both in the West and in Washington, DC.

But…

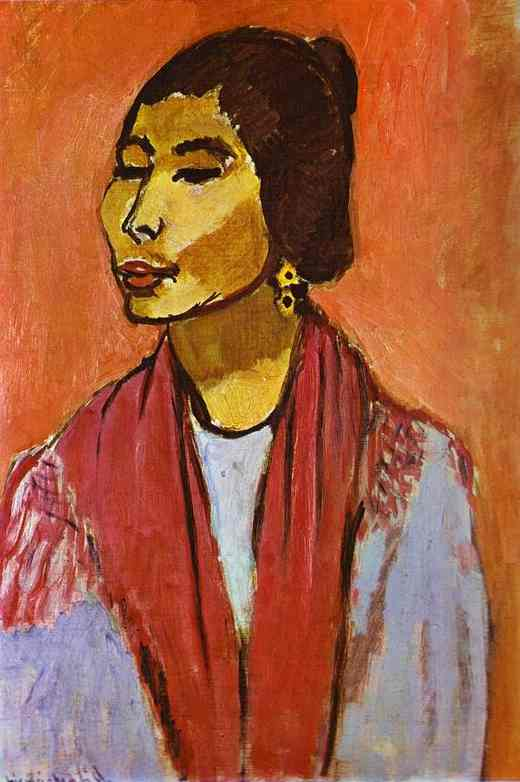

Then came the slap in the face that was Matisse. More vituperation had been directed at this painter, in reviews of the show so far, than at any other “Cubist”--a term that actually did not apply to him, but nevertheless was used as an epithet. Roosevelt gazed at his “Joaquina”

And found its cartoony angularity simply absurd. Beyond loomed a kneeling nude by Wilhelm Lehmbruck.

Although obviously mammalian, it was not especially human; the “lyric grace” that had made it the sensation of a recent exhibition in Cologne reminded him more of a praying mantis.

A phrase he had recently tried out on Henry Cabot Lodge, in a letter complaining about political extremists, came to mind: lunatic fringe. It seemed even more applicable to the French radicals who now proceeded to insult his intelligence, as if he and not they were insane: Picasso, Braque, Brancusi, Maillol. He boggled at Marcel Duchamp’s Nu descendant un escalier,

a shuttery flutter of cinematic movement propelled by the kind of arcs that American comic artists drew to telegraph punches, or baseball swings. If this was Cubism, or Futurism, or Near-Impressionism, or whatever jargon-term the theorists of modern art wanted to apply to it, he believed he had seen it before, in a Navajo rug.

To our modern eyes, the stylistic progression from the works Roosevelt appreciated to the ones that shocked his sensibilities is neither dramatic nor difficult to discern. But even for Roosevelt, a man who straddled two centuries perhaps better than any American before or after, Cubism was clearly a bridge too far. After deconstructing European formalism to create something uniquely American, he evidently wasn’t ready to deconstruct that American ideal, even for the chance of transcending it to something greater.

Which brings me back to the dissertation idea I started with. In Europe in 1910, he was screened-off from the extraordinary changes occurring in society. In America in 1913, he was blind to them.

The Aging Progressive

Which is a bit of a surprise.

After the crush and his loss in the 1912 presidential campaign, Roosevelt turned more of his attention to his literary pursuits, accepting remuneration for writing essays of his own choosing for several popular magazines. His disagreements with Sonya Levein--a Russian-born radical whom he called “Little Miss Anarchist” and, who served as his editor for the Metropolitan--are equally revealing of the increasing distance the progressivism of the age was putting on the aging ex-president.

She saw that Roosevelt could not understand the difference between the kind of boredom he complained of on the campaign trail, and the spiritual despair of miners and factory workers who saw nothing ahead of them but brute labor and an unpaid old age. His response to her attempts to enlighten him on that score was invariable: that the life of the working poor could be improved by social legislation, but that ultimately every man’s success or failure depended upon “character.”

It’s an interesting perspective because, of course, Roosevelt, in the vigor of his youth and his presidency, was a progressive. One of things I have always found fascinating about him is the way he tried to balance the conservatism of America’s origin myths with the emerging progressiveness of an interventionist government. Unlike many of the politicians of his day (and today) he was both an individualist and a collectivist, mixing the two philosophies together in what he deemed to be the right mixture for American prosperity and exceptionalism. In this way he may have been the First Progressive (or the Last Romantic; take your pick), paving the way for collectivist excesses of Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, their assimilation into a broad political consensus safeguarded by Truman and Eisenhower, then fractured by Goldwater, Nixon and Reagan, and its ultimate degeneration into the polar opposite political camps we endure today.

I believe Theodore Roosevelt can be viewed as the first link in this chain, the opening chapter in the long history of the American political climate in the 20th century.

Want an example of this progressiveness? As Morris details in the first half of his book, long before Roosevelt came under Levien’s editorial rancor, he went through a period of being very disturbed and distressed about no longer being the president of the United States. As a result, he quickly re-entered politics, first as a public speaker, then to stump for other Republican candidates, and finally to campaign for a then-unprecedented third term as president.

And this must have been a time when he felt his progressive legacy most poignantly. Here’s a revealing couple of paragraphs from Morris’s summary of one of those early public speeches in Colorado.

It was a looming third crisis he wished to discuss--one utterly modern, yet still subject to the wisdom of Abraham Lincoln. The Emancipator had advocated harnessing a universal dynamic, whose power derived from the struggle between those who produced, and those who profited. Roosevelt quoted Lincoln’s famous maxim, Labor is the superior of capital, and joked, “If that remark was original with me, I should be even more strongly denounced as a communist agitator than I shall be anyhow.”

Nevertheless, he was willing to go further in insisting that property rights must henceforth be secondary to those of the common welfare. A maturing civilization should work to destroy unmerited social status. “The essence of any struggle for healthy liberty has always been … to take from some one man or class the right to enjoy power, or wealth, or position, or immunity, which has not been earned by service to his or their fellows.”

America’s corporate elite, Roosevelt said, was fortifying itself with the compliance of political bosses. He revived one of his favorite catchphrases: “I stand for the square deal.” Granting that even monopolistic corporations were entitled to justice, he denied them any right to influence it, or to assume that they could buy votes in Congress.

“The Constitution guarantees protections to property, and we must make that promise good. But it does not give the right of suffrage to any corporation. The true friend of property, the true conservative, is he who insists that property shall be the servant and not the master of the commonwealth; who insists that the creature of man’s making shall be the servant and not the master of the man who made it. The citizens of the United States must effectively control the mighty commercial forces which they have themselves called into being.”

Despite being a Republican, these views did not belong in the Republican party of Roosevelt’s day, much less the Republican party of our day. And in them, I think it’s plain to see, many of the controversies and differences of opinion that Republicans and Democrats are still debating to this day. Property rights must henceforth be secondary to those of the common welfare? Supreme Court justices are appointed or rejected based on their view on this question. And the paragraph about corporations being given the right to vote, about becoming the masters of the people who created them, brings to mind the recent controversies over Citizens United and Hobby Lobby. What, one wonders, would Teddy Roosevelt have made of those decisions?

The Will of the People

Another way that Roosevelt was different from most modern politicians is that he honored the proud Jeffersonian tradition of not publicly seeking an office he desperately craved.

Within two days of the opening of his national headquarters in Chicago, the pressure on Roosevelt to declare had increased to such a point that he decided to yield--but only to a petition that made clear his reluctance to run. He asked the four Republican governors who were most energetically championing him (Chase Osborn of Michigan, Robert P. Bass of New Hampshire, William E. Glasscock of West Virginia, and Walter R. Stubbs of Kansas) to send him a written appeal for his candidacy. If they would argue that they were acting on behalf of the “plain people” who had elected them, he would feel “in honor bound” to say yes.

Here we see the ulitmate hypocrisy of political ambition writ large.

Roosevelt maintained for the rest of the month that he was not a candidate. “Do not for one moment think that I shall be President next year,” he cautioned Joseph Bucklin Bishop, one of his most obsequious acolytes. “I write you, confidentially, that my own reading of the situation is that while there are a great many people in this country who are devoted to me, they do not form more than a substantial minority of the ten or fifteen millions of voters. … Unless I am greatly mistaken, the people have made up their mind that they wish some new instrument, that they do not wish me; and if I know myself, I am sincere when I tell you that this does not cause one least little particle of regret to me.”

Of course, Roosevelt is only setting the stage here. Telling one of his acolytes (wink, confidentially) that he does not believe he will be offered nor will he seek the nomination for president, knowing full well that soon his secretly-asked-for petition will arrive. Me? he will likely exclaim in tones devoid of any political ambition. The country wants me?

A fascinating subject, and perhaps worthy of another PhD thesis, would be trying to determine if Roosevelt actually believed this. His ensuing rhetoric on the campaign trail, following the arrival of his manufactured “people’s petition,” is enough to make one think he might be self-deluded on this very point.

Roosevelt’s sharp voice scratched every sentence into the receptivity of his listeners, and his habit of throwing sheet after sheet of manuscript to the floor seemed to mime points raised and dealt with. His peroration brought even [Republican boss William] Barnes to his feet in applause:

“The leader for the time being, whoever he may be, is but an instrument, to be used until broken and then to be cast aside; and if he is worth his salt he will care no more when he is broken than a soldier cares when he is sent where his life is forfeit in order that the victory may be won. In the long fight for righteousness the watchword for all of us is “Spend and be spent.”

Here is the true emblem of leadership--for the cause, not for myself--delivered so persuasively that even hardened political bosses are brought to their feet. And when learning of some distressing early primary defeats:

“They are stealing the primary elections from us,” [Roosevelt] said. “All I ask is a square deal. … I cannot and will not stand by while the opinion of the people is being suppressed and their will thwarted.”

It is a slight not against Roosevelt the candidate, but against the “will of the people.”

I don’t buy it. I think Roosevelt was a skilled enough politician to dose his subterfuge with sincerity, while being smart enough to convince everyone except himself. And, evidently, I wasn’t the only one. There were plenty of people in Roosevelt’s age who saw through the calculation, who saw the hubris that boiled away beneath the humility.

As Roosevelt continued to rack up primary wins, trumpeting each victory as a personal triumph, [Harper’s Weekly cartoonist E. W.] Kemble began a savage series of caricatures portraying him as a self-obsessed spoiler. Grinning toothily, “Theodosus the Great” crowned himself with laurels; he toted a tar-bucket of abuse and splattered it, black and dripping, across the Constitution, Supreme Court, and White House. He emboldened every capital I in a screed reading:

I am the will of the

people I am the leader

I chose myself to be

leader it is MY

right to do so. Down with

the courts, the bosses

and every confounded thing that opposes

ME. I AM IT

do you get me?

I will have as many terms

in office as I

desire. Sabe!

T.R.

And, as nauseating as the hypocrisy is, it might be refreshing for some of our modern politicians to take a similar tack. But perhaps, just as our modern politicians are creatures of their own age, perhaps Roosevelt (and Jefferson) were just creatures of theirs. Was there a time in American history when people whowanted to be president could not say that they desired the position or the power, since that, above all, would turn the electorate against them? It is only when others say they want someone else to be president, even over that person’s initial objections, that we believe the person in question might have the character to be president?

Maybe things haven’t changed so much after all. I’ve noticed that as my mind becomes more and more politically aware--or politically cynical, as I’m sure many who know me would say--I see more and more parallels to our modern world in the political machinations of the past.

President Taft told Archie Butt that Roosevelt was delusional if he thought he could control the forces of anarchy he had unleashed. “He will either be a hopeless failure if elected or else destroy his own reputation by becoming a socialist, being swept there by the force of circumstances just as the leaders of the French Revolution were swept on and on.”

A fairly inconspicuous paragraph. Advice from the sitting president back to his predecessor, political mentor, and possible successor. But in it I see a penetrating commentary on the political extremism of today’s candidates. I’m writing at the end of February 2016, although this will probably post sometime in May, and there are extremists currently leading in the presidential nomination process for both the Republican and Democratic parties. Should either be elected, I wonder, in Taft’s words, where their extremism will “sweep” them. One preaches isolationist-know-nothing-ism and the other is an avowed socialist, and they both have vocal prescriptions for our country whose popularity only seems to benefit from their impracticability. Just as Taft feared that Roosevelt would not be able to control the forces of “anarchy” he was tampering with, I fear the opposite forces of populism these candidates are tampering with, and I question whether either of them will be able to control these forces once elected and the campaign promise checks start coming due.

Cavalry Charges vs. Mustard Gas

But just as Roosevelt was a kind of visionary when it came to progressive politics, he was, in my opinion, a kind of regressive romantic when it came to his views on war. Morris summarizes it well.

Like many men of martial instinct, the Colonel claimed to be peaceable. But it was plain to everybody that he loved war and thought of it as a catharsis. War purged the fat and ill humors of a sedentary society whose values had been corrupted by getting and spending. Waged for a righteous cause, it reawakened moral fervor, intensified love and loyalty, concentrated the mind on fundamental truths, strengthened the body both personal and political. It was, in short, good for man, good for man’s country, and often as not, good for the vanquished too. In celebrating its terrible beauty, Roosevelt often came near the sentimentality he despised among pacifists--so much so that some of his most affectionate friends felt their gorges rise when he romanticized death in battle.

War as catharsis. It’s a quaint idea. For the great men of history, perhaps, it is a catharsis. But for its millions of other victims, names unknown? And for its billions of victors and vanquished, generations of them, that must live in the world that war has shattered?

People like Sonya Levien saw this regressivism for what it was--a relic of an old way of life that could no longer meet this challenges of an increasingly modern world. In the years after Woodrow Wilson’s election as president, as American involvement in World War I became more and more inevitable, Roosevelt still nurtured these quaint ideas.

He had not forgotten his dream of leading a force of super-Rough Riders into battle, and took it for granted that the War Department would allow him to do so as a major-general. The plan sounded old, even antiquated, when he spelled it out to General Frank Ross McCoy on 10 July [1915]. “My hope is, if we are to be drawn into this European war, to get Congress to authorize me to raise a Cavalry Division, which would consist of four cavalry brigades each of two regiments, and a brigade of Horse Artillery of two regiments, with a pioneer battalion or better still, two pioneer battalions, and a field battalion of signal troops in addition to a supply train and a sanitary train.”

Roosevelt vaguely explained that he meant motor trains, “and I would also like a regiment or battalion of machine guns.” But it was obvious he still thought the quickest path to military glory was the cavalry charge--ignoring the fact that modern Maxim-gun fire had proved it to be an amazingly effective form of group suicide. And he also chose to forget that the last time he had tried to haul his heavy body onto a horse, at Sagamore Hill in May, he had ended up on the ground with two broken ribs.

There are few other appropriate words than “delusional” for this line of thinking. In his day, charging up San Juan Hill was certainly dangerous and brave. But, by 1915, the meatgrinder of machine guns and trench warfare was upon the world, and any military leader worth his salt would have been required to change not only his tactics but his outlook as well. On San Juan Hill, war turned boys into men. At Verdun it turned them into hamburger.

So when Roosevelt made public statements about the Great War, statements like this...

“I have always wanted to be with Mrs. Roosevelt and my children, and now with my grandchildren. I’m not a brawler. I detest war. But if war came I’d have to go, and my four boys would go, too, because we have ideals in this family.”

...one has to wonder if he truly grasped the price those ideals would cost him and his family.

When American forces advanced through the tiny village of Chamery, in the Marne province of France, they came upon a cross-shaped fragment of a Nieuport fighter sticking out of a field just east of the road to Coulonges. Some German soldier had taken a knife and scratched on it the words ROOSEVELT. It marked [the grave of Roosevelt’s youngest son, Quentin], and a few yards away the rest of his plane lay wrecked. … The autopsy performed by the Germans before Quentin’s burial indicated that he had been killed before he crashed. Two bullets had passed through his brain. He had been thrown out on impact, and photographed where he fell.

It was an event that might have shattered Roosevelt’s war spirit, to make him finally come to embrace the abject futility of war that the machines, like Quentin’s own Nieuport fighter, had created--if he himself would not be dead within six short months.

But in November 1916, campaigning against Wilson’s re-election, that anger had not yet been slaked. Quite the reverse, it was stoked to white-hot intensity by the deaths of other innocents.

A sense spread through the audience that Roosevelt was going to let rip, as he had when he jumped onto a table in Atlanta in 1912. But nothing he had said then, or since, compared with the attack on Woodrow Wilson that now rasped into every corner of the hall.

“During the last three years and a half, hundreds of American men, women, and children have been murdered on the high seas and in Mexico. Mr. Wilson has not dared to stand up for them. … He wrote Germany that he would hold her to ‘strict accountability’ if an American lost his life on an American or neutral ship by her submarine warfare. Forthwith the Arabic and the Gulflight were sunk. But Mr. Wilson dared not take any action. … Germany despised him; and the Lusitania was sunk in consequence. Thirteen hundred and ninety-four people were drowned, one hundred and three of them babies under two years of age. Two days later, when the dead mothers with their dead babies in their arms lay by the scores in the Queenstown morgue, Mr. Wilson selected the moment as opportune to utter his famous sentence about being ‘too proud to fight.’”

Roosevelt threw his speech script to the floor and continued in near absolute silence.

“Mr. Wilson now dwells at Shadow Lawn. There should be shadows enough at Shadow Lawn: the shadows of men, women, and children who have risen from the ooze of the ocean bottom and from graves in foreign lands; the shadows of the helpless whom Mr. Wilson did not dare protect lest he might have to face danger; the shadows of babies gasping pitifully as they sank under the waves; the shadows of women outraged and slain by bandits; the shadows of … troopers who lay in the Mexican desert, the black blood crusted round their mouths, and their dim eyes looking upward, because President Wilson had sent them to do a task, and then shamefully abandoned them to the mercy of foes who knew no mercy.

“Those are the shadows proper for Shadow Lawn: the shadows of deeds that were never done; the shadows of lofty words that were followed by no action; the shadows of the tortured dead.”

The note I scribbled in the margin beside this remarkable passage is short and simple. Wow. We might well imagine politicians of today uttering words like these against their rivals, but in 1916 it must have been unthinkable. And indeed, Charles Evans Hughes, the Republican candidate that Roosevelt had been stumping for, lost the election a few days later to Woodrow Wilson.

But then returns from late-counting states showed that Republicans and former Progressives had deserted Hughes in the Midwest, canceling out his early gains elsewhere. The great bulk of those desertions could be ascribed to Roosevelt’s warlike rhetoric, which had made Hughes’s candidacy seem more pro-intervention that it actually was. In the end, after two days of statistical swings, the normally Republican state of California reelected Wilson by a margin of only 3,773 votes. Hughes was so angry in defeat that he did not concede until 22 November.

“I hope you are ashamed of Mr. Roosevelt,” Alice Hooper wrote Frederick Jackson Turner. “If one man was responsible for Mr. Wilson he was the man--thus perhaps Mr. Roosevelt ought to see the Shadows of Shadow Lawn and the dead babies in the ooze of the Sea!”

This, to me, is the most remarkable aspect of this episode. In 1916, it was saber-rattling that lost elections--something Wilson clearly understood as he “dared not take any action.” A hundred years later, in 2016, it sometimes feels like saber-rattling is the surest way to win an election.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Surrounded by flunkeys, guarded wherever he went, Roosevelt was screened off from the extraordinary changes occurring at lower levels of Viennese society--changes more radical than anywhere else in Europe, and coincident with Austria-Hungary’s thrust into the Balkans. He did not see the pornographic nudes of Klimt and Schiele, Kokoschka’s explosive studies of angst-filled burghers, the rectilinear architecture of the Secessionists. He was deaf to the atonality of Schonberg and the warnings of local poets and playwrights that an apocalypse was coming.

And in this paragraph, I discovered another one of those PhD theses I would have written in another life. Does the content and style of progressive art in one era accurately predict the historical events and conflicts of the next?