I recently got elected to another association board. After a tour of duty on the board of the Wisconsin Society of Association Executives (including one year as board chair), I've moved onto the board of the Council of Manufacturing Associations (CMA). They're a child of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), with a membership comprised of the chief staff executives and senior-level staff of the manufacturing-based trade associations that are members of NAM.

I'm looking forward to the experience. I've been attending CMA events for 10 years now--for as long as I've been the chief staff executive of my own manufacturing-based trade association--and I've found a lot of value in them. The education, peer networking, and vendor contacts are all top notch, and I've taken professional advantage of all three over the span of my relationship with them.

But I don't know what kind of board experience it will be. Like a lot of people in my situation, I kept my mouth mostly shut in my very first board meeting, paying more attention to the personalities and protocols I was seeing on display for the first time.

It was a good reminder of the dynamic we often see with our own boards, the newcomer sitting there, listening, and trying to absorb how this board functions and how much weight any one voice has. As the staff person I sometimes wonder what's wrong with that new board member. Don't they know we put them on the board because we wanted to hear their opinion? But as the new board member himself, I was reminded of how difficult speaking up is when you don’t know the ground rules.

We had a short orientation meeting before the board meeting, which was helpful and considerate. But, upon reflection, I realize that it was lacking one of the most important pieces of information about being a constructive board member. What is the organization trying to achieve and what role do board members play in helping it get there?

Tell me that and I'm ready to dive in with both feet.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://www.hercampus.com/career/job-advice/4-success-tips-introverted-interns

Monday, January 30, 2017

Why New Board Members Don't Speak Up

Labels:

Associations,

Leadership

Monday, January 23, 2017

Association Staff and the Marriage of Strategy and Resources

I had another experience this week that helped reinforce the important role that association staff must play in successfully marrying strategy to resources.

My association recently applied for a federal grant to fund a program we deem important to our educational mission. When discussed at our most recent Board meeting, it was determined that the program represented an ideal way of executing one of the association's key strategic objectives. So much so, in fact, that the Board decided that the program should advance, in whatever form it could, even if the federal funds were not awarded.

That's where me and my staff stepped in. The reason we applied for the federal grant was we didn't have the resources necessary to execute the program on our own. With the new strategic decision by our Board, we had to take another look at how our resources could be better utilized for supporting the new program. That generally meant two things.

1. Reduce the resources needed to successfully manage the program. What could we do to lower the cost of managing the program without overly diluting its anticipated effectiveness? This was certainly a bit of a guessing game, since it is a new program -- based on a successful pilot -- that we haven't worked on before. But, by looking carefully at our expected outcomes we were able to strip out some costs that seemed less directly connected to our goals. We also reduced the overall scope of the program -- thinking regionally rather than nationally -- both as a way to reduce costs, but also to give us closer oversight and control.

2. Repurpose resources allocated for other programs to the new one. What were we currently doing that we could stop doing in order to provide more support for the new program? This was an even greater challenge than just stripping costs out of the new program, because everything else we do already has a validated strategic purpose and a set of stakeholders that support it. Rather than suggesting we sacrifice items from wildly different parts of the organization, we instead focused on resources and programs within the same department in which the new program would live. When looking at how the new program could support or compete with established activities in the same strategic envelope, we were able to identify several areas that should logically be re-purposed in order to make a more efficient whole.

It was an exciting and productive exercise, and the revised budgets and proposals are going back to our Board next week. It will be interesting to see what they make of it. To me, if nothing else, it was a textbook example of the level of decision-making that is best performed at the staff level of an association.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://www.rolereboot.org/culture-and-politics/details/2014-09-proud-people-getting-married/

My association recently applied for a federal grant to fund a program we deem important to our educational mission. When discussed at our most recent Board meeting, it was determined that the program represented an ideal way of executing one of the association's key strategic objectives. So much so, in fact, that the Board decided that the program should advance, in whatever form it could, even if the federal funds were not awarded.

That's where me and my staff stepped in. The reason we applied for the federal grant was we didn't have the resources necessary to execute the program on our own. With the new strategic decision by our Board, we had to take another look at how our resources could be better utilized for supporting the new program. That generally meant two things.

1. Reduce the resources needed to successfully manage the program. What could we do to lower the cost of managing the program without overly diluting its anticipated effectiveness? This was certainly a bit of a guessing game, since it is a new program -- based on a successful pilot -- that we haven't worked on before. But, by looking carefully at our expected outcomes we were able to strip out some costs that seemed less directly connected to our goals. We also reduced the overall scope of the program -- thinking regionally rather than nationally -- both as a way to reduce costs, but also to give us closer oversight and control.

2. Repurpose resources allocated for other programs to the new one. What were we currently doing that we could stop doing in order to provide more support for the new program? This was an even greater challenge than just stripping costs out of the new program, because everything else we do already has a validated strategic purpose and a set of stakeholders that support it. Rather than suggesting we sacrifice items from wildly different parts of the organization, we instead focused on resources and programs within the same department in which the new program would live. When looking at how the new program could support or compete with established activities in the same strategic envelope, we were able to identify several areas that should logically be re-purposed in order to make a more efficient whole.

It was an exciting and productive exercise, and the revised budgets and proposals are going back to our Board next week. It will be interesting to see what they make of it. To me, if nothing else, it was a textbook example of the level of decision-making that is best performed at the staff level of an association.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://www.rolereboot.org/culture-and-politics/details/2014-09-proud-people-getting-married/

Labels:

Associations,

Strategy and Execution

Saturday, January 21, 2017

Fiasco by Thomas E. Ricks

President George W. Bush’s decision to invade Iraq in 2003 ultimately may come to be seen as one of the most profligate actions in the history of American foreign policy. The consequences of his choice won’t be clear for decades, but it already is abundantly apparent in mid-2006 that the U.S. government went to war in Iraq with scant solid international support and on the basis of incorrect information--about weapons of mass destruction and a supposed nexus between Saddam Hussein and al Qaeda’s terrorism--and then occupied the country negligently. Thousands of U.S. troops and an untold number of Iraqis have died. Hundreds of billions of dollars have been spent, many of them squandered. Democracy may yet come to Iraq and the region, but so too may civil war or a regional conflagration, which in turn could lead to spiraling oil prices and a global economic shock.

That’s the opening paragraph of Ricks’s journalistic expose, which he subtitles “The American Military Adventure in Iraq.”

The book’s subtitle terms the U.S. effort in Iraq an adventure in the critical sense of adventurism--that is, with the view that the U.S.-led invasion was launched recklessly, with a flawed plan for war and a worse approach to occupation. Spooked by its own false conclusions about the threat, the Bush administration hurried its diplomacy, short-circuited its war planning, and assembled an agonizingly incompetent occupation. None of this was inevitable. It was made possible only through the intellectual acrobatics of simultaneously “worst-casing” the threat presented by Iraq while “best-casing” the subsequent cost and difficulty of occupying the country.

And that’s the second. Together, they comprise an excellent summary of both the underlying thesis of this book, as well as the accusations that prove to be well-substantiated in Ricks’s ensuing narrative and research.

It’s a book that left me with a handful of major takeaways.

1. The Congressional vote to provide President Bush with the authority to go to war didn’t succeed because those voting had any deep insight or understood the historical import of what they were doing.

The exchanges on the Senate floor offered little of the memorable commentary seen in the two other most recent congressional debates on whether to go to war, in 1991 and in 1964, regarding the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. “The outcome--lopsided support for Bush’s resolution--was preordained,” wrote the Washington Post’s Dana Milbank. Republicans were going to support the president and their party, and Democrats wanted to move on to other issues that would help them more in the midterm elections that at that point were just three weeks away.

As I’ve discovered elsewhere in my journeys through American history, Congress typically passes things--even historic pieces of legislation--because of in-the-moment and historically forgotten political calculations. We say we want our Representatives and Senators to show political courage, to cast the tough votes based on conscience and political ideology, but too often they simply don’t. They vote the way they do because each vote is going to help them or their objectives in the short term. It’s something that I’ve encountered time and time again, and it persists even, as it did for some in Ricks’s account, the failure to stick to principles comes back to bite those who should have shown more courage.

One of those voting for [the authorization] was … Max Cleland, who was in a tight campaign for reelection in which his challenger, Saxby Chambliss, was running commercials that showed images of Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein and implied that Cleland wasn’t standing up to them. Despite his misgivings, Cleland felt under intense political pressure to go with the administration. “It was obvious that if I voted against the resolution that I would be dead meat in the race, just handing them a victory,” he said in 2005. Even so, he now considers his prowar choice “the worst vote I cast.” …

Despite his vote for war, the next month Cleland lost his Senate race by a margin of 53 percent to 46 percent, in part because of a statewide controversy over the Confederate battle flag that helped get out the rural white vote. He said he took it harder than being blown up by a hand grenade in Vietnam. “I went down--physically, mentally, emotionally--down into the deepest, darkest hole of my life,” he recalled. “I had several moments when I just didn’t want to live.”

This should not only be a fundamental lesson for those who find themselves in Congress and who want to make history, it should also be a fundamental lesson for anyone who wants to get any kind of legislation passed. For those in Congress, please, vote your conscience, that’s what we elected you to do. And for the legislators, always downplay the historical importance of your legislation and always schedule the vote when the political facts on the ground are in your favor.

2. Despite this historical reality about how Congress behaves--Congress was especially asleep at the wheel during the Iraq war.

In previous wars, Congress had been populated by hawks and doves. But as war in Iraq loomed it seemed to consist mainly of lambs who hardly made a peep. There were many failures in the American system that led to the war, but the failures in Congress were at once perhaps the most important and the least noticed.

One of the rules of thumb in military operations is that disasters occur not when one or perhaps two things go wrong--which almost any competent leader can handle--but when three or four things go wrong at once. Overcoming such a combination of negative events is a true test of command. Similarly, the Iraq fiasco occurred not just because the Bush administration engaged in sustained self-deception over the threat presented by Iraq and the difficulty in occupying the country, but also because of other major lapses in several major American institutions, from the military establishment and the intelligence community to the media. In each arena, the problems generally were sins of commission--bad planning, bad leadership, bad analysis, or in the case of journalism, bad reported and editing. The role of Congress in this systemic failure was different, because its mistakes were mainly sins of omission. In the months of the run-up to war, Congress asked very few questions, and didn’t offer any challenge to the administration on the lack of postwar planning.

3. The villains in Ricks’s tale are largely the civilians in the upper ranks of the Bush administration.

Primarily Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld...

Ultimately, however, the fault for the lapse in the planning must lie with Rumsfeld, the man in charge. In either case, it is difficult to overstate what a key misstep this lack of strategic direction was--probably the single most significant miscalculation of the entire effort. In war, strategy is the searchlight that illuminates the way ahead. In its absence, the U.S. military would fight hard and well but blindly, and the noble sacrifices of soldiers would be undercut by the lack of thoughtful leadership at the top that soberly assessed the realities of the situation and constructed a response.

Strategic leadership was apparently one of Rumsfeld’s weaker suits. But so was a confused reporting structure that, it seems, even he did not understand.

In a meeting in the White House situation room one day, there was a lot of “grousing” about [Coalition Provisional Authority Chief L. Paul] Bremer, a senior administration official who was there recalled. As the meeting was breaking up [Condoleezza] Rice, the national security adviser, reminded Rumsfeld that Bremer reported to him. “He works for you, Don,” Rice said, according to this official.

“No, he doesn’t,” Rumsfeld responded--incorrectly--this official recalled. “He’s been talking to the NSC, he works for the NSC.”

Bremer relates a similar anecdote in his memoir, saying that Rumsfeld told him later in 2003 that he was “bowing out of the political process,” which apparently meant he was detaching from dealing with Iraq--a breathtaking step for the defense secretary to take after years of elbowing aside the State Department and staffers on the National Security Council.

Speaking of Bremer, he is clearly another civilian villain in Ricks’s tale.

One of the first things Bremer did after arriving in Iraq was show [Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance Chief Jay] Garner the order he intended to issue to rid Iraq if Baathist leadership. “Senior Party Members,” it stated, “are hereby removed from their positions and banned from future employment in the public sector.” In addition, anyone holding a position in the top three management layers of any ministry, government-run corporation, university or hospital and who was a party member--even of a junior rank--would be deemed to be a senior Baathist and so would be fired. What’s more, those suspected of crimes would be investigated and, if deemed a flight risk, would be detained or placed under house arrest.

Garner was appalled. …

If issued as written, the order Bremer was carrying would lead to disaster, Garner thought. He went to see the CIA station chief, whom Garner had seen work well with the military. “This is too hard,” Garner told the CIA officer, who read it and agreed. The two allies went back to Bremer.

“Give us an hour or so to redo this,” Garner asked.

“Absolutely not,” Bremer responded. “I have my instructions, and I am going to issue this.”

The CIA station chief urged Bremer to reconsider. These are the people who know where the levers of the infrastructure are, from electricity to water to transportation, he said. Take them out of the equation and you undercut the operation of this country, he warned.

No, said Bremer.

Okay, the veteran CIA man responded. Do this, he said, but understand one thing: “By nightfall, you’ll have driven 30,000 to 50,000 Baathists underground. And in six months, you’ll really regret this.” ...

Bremer looked at the two. “I have my instructions,” he repeated, according to Garner, though it isn’t clear that he really did, as the policy he was implementing wasn’t what had been briefed to the president. A few months later, the veteran CIA man would leave Baghdad, replaced by a far more junior officer. In the fall of 2005 he would resign from government service.

To hear Ricks tell it, these men, and others like them, had all been placed in positions above their competency levels, and none of them possessed the humility to even try to understand the actual situation on the ground.

There is an interesting passage in Ricks’s account that demonstrates the disastrous and tragic results of Bremer’s decision to “de-Baathify” the country.

At the end of May and in early June [of 2003], dismissed ministry workers and former Iraqi army soldiers [who Bremer also autocratically put out of work] held a series of demonstrations. Some vowed they would violently oppose the U.S. decisions. “All of us will become suicide bombers,” former officer Khairi Jassim told Reuters. The wire service article was distributed at the CPA [the Coalition Provisional Authority] with that quotation highlighted.

“The only thing left for me is to blow myself up in the face of tyrants,” another officer told Al Jazeera.

Bremer insisted he wouldn’t be moved. “We are not going to be blackmailed into producing programs because of threats of terrorism,” he said at a press conference in early June.

The protests continued. On June 18 an estimated two thousand Iraqi soldiers gathered outside the Green Zone to denounce the dissolution decision. Some carried signs that said, PLEASE KEEP YOUR PROMISES. Others threw rocks. “We will take up arms,” Tahseen Ali Hussein vowed in a speech to the demonstrators, according to an account by Agence France Presse. “We are all very well-trained soldiers and we are armed. We will start ambushes, bombings and even suicide bombings. We will not let the Americans rule us in such a humiliating way.” U.S. soldiers fired into the crowd, killing two.

What I find so fascinating about this passage, I think, is the way the two sides are so tragically talking past each other, each using words that mean something quite different in the opposite’s culture.

Please keep your promises, the Iraqis are saying. You are humiliating us.

We will take up arms, the Americans are hearing. We will become suicide bombers. And, as a result, are saying in return, We will not be blackmailed by threats of terrorism.

4. In contrast to these civilian leaders, Ricks portrays many of the military leaders as the pyrrhic heroes of the tale, having done the best they could under the very difficult situations created for them.

And unlike their civilian leaders, they understood the situation on the ground and the people they would come to fight. One shining example is Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Holshek, who took exception to the way his commanding officer was treating the civilian Iraqi population.

He asked his commander to imagine himself the head of a household in an Iraqi village. “Two o’clock in the morning, your door bursts open. A bunch of infantry guys burst into the private space of the house--in a society where family honor is the most important thing--and you lay the man down, and put the plastic cuffs on? And then we say, ‘Oops, wrong home?’ In this society, the guy has no other choice but to seek restitution. He will do that by placing a roadside bomb for one hundred dollars, because his family honor has been compromised, to put it mildly.” Simply to restore his own self-respect, the Iraqi would then have to go out and take a shot at American forces.

What was Colonel Holshek’s preferred method for dealing with these situations?

The wrong doors continued to be smashed on occasion, but when they were, Holshek would issue a letter that stated, “We are sorry for the intrusion, we are trying to help here, and it is a difficult business, and we sometimes make mistakes. If you have information that would help us, we would be grateful.” The cash equivalent in dinars of one hundred dollars would accompany the note. Those gestures of regret didn’t really win over Iraqis, Holshek recalled later, but he said he thought they did tend to tamp down anger, and so curtail acts of revenge.

Because that’s the essential point. Certainly in the beginning, before there was an organized counterinsurgency, and throughout the occupation among certain civilian populations, the attacks on American forces were not acts of terrorism, but those of revenge against aggrieved honor.

[Major Isaiah] Wilson, the historian and 101st planner, later concluded that much of the firing on U.S. troops in the summer and fall of 2003 consisted of honor shots, intended not so much to kill Americans as to restore Iraqi honor. “Honor and pride lie at the center of tribal society,” he wrote. In a society where honor equals power, and power ensures survival, the restoration of damaged honor can be a matter of urgency. But that didn’t mean that Iraqis insulted by American troops necessarily felt they had to respond lethally, Wilson reflected. “Honor that is lost or taken must be returned by the offender, through ritualistic truce sessions, else it will be taken back through force of arms.” In Iraq this sometimes was expressed in ways similar to the American Indian practice of counting coup, in which damaging the enemy wasn’t as important as demonstrating that one could. So, Wilson observed, an Iraqi would take a wild shot with a rocket-propelled grenade, or fire randomly into the air as a U.S. patrol passed. “Often the act of taking a stand against the ‘subject of dishonor’ is enough to restore the honor to the family or tribe,” whether or not the attack actually injured someone, he wrote. “Some of the attacks that we originally saw as ‘poor marksmanship’ likely were intentional misses by attackers pro-progress and pro-U.S., but honor-bound to avenge a perceived wrong that U.S. forces at the time did not know how to appropriately resolve.” But U.S. troops assumed simply that the Iraqis were bad shots.

I find this fascinating, this cultural divide between the Americans and the Iraqis, how it affected the progress of the war, and how few people in the U.S. apparatus seemed to understand the fundamental premise that the people they encountered were simply that--people.

[Captain Oscar Estrada] thought about an incident a few weeks earlier on the road east of Baqubah the soldiers called RPG Alley. The groves of date palms along the road provided insurgents with hiding places from which to fire their rocket-propelled grenades. When a unit ahead of them in a convoy reported taking fire from one such grove, he recalled, everyone began firing--automatic weapons, grenades, and .50 caliber heavy machine guns.

“What the hell are we shooting at?” he had screamed at a buddy as he fired his M-16.

“I’m not sure,” the soldier had responded. “By the shack. You?”

“I’m just shooting where everybody else is shooting,” Estrada had said, continuing to squeeze off rounds.

When the firing ended, he heard the commander on the radio. “Dagger, this is Bravo 6. Do you have anything, over?”

“Roger. … We have a guy here who’s pretty upset. I think we killed his cow, over.”

“Upset how, over?”

“He can’t talk. I think he’s in shock. He looks scared, over.”

“He should be scared. He’s the enemy.”

“Uhm, ahh, roger, 6. … He’s not armed and looks like a farmer or something.”

“He was in the grove that we took fire from. He’s a fucking bad guy.”

A fucking bad guy. We all know what you do when you encounter a bad guy, right? You shoot him. Good guys always shoot the bad guys. It helps keep their sisters and girlfriends safe.

“Roger.”

Estrada wondered what was gained from that minor incident, and what was lost. “Did his family depend on that cow for its survival? Had he seen his world fall apart? Had we lost both his heart and his mind?” Fundamentally, Estrada was asking himself whether the U.S. Army should be in Iraq, and if so, whether it was approaching the occupation of Iraq in the right way. “I was beginning to come to terms with serious doubts about our cause,” he later said, “and whether even if I accepted that our cause was just, our day-to-day actions did anything to champion it.”

After reading Ricks’s book, I find that Captain Estrada is not the only person asking these questions.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

That’s the opening paragraph of Ricks’s journalistic expose, which he subtitles “The American Military Adventure in Iraq.”

The book’s subtitle terms the U.S. effort in Iraq an adventure in the critical sense of adventurism--that is, with the view that the U.S.-led invasion was launched recklessly, with a flawed plan for war and a worse approach to occupation. Spooked by its own false conclusions about the threat, the Bush administration hurried its diplomacy, short-circuited its war planning, and assembled an agonizingly incompetent occupation. None of this was inevitable. It was made possible only through the intellectual acrobatics of simultaneously “worst-casing” the threat presented by Iraq while “best-casing” the subsequent cost and difficulty of occupying the country.

And that’s the second. Together, they comprise an excellent summary of both the underlying thesis of this book, as well as the accusations that prove to be well-substantiated in Ricks’s ensuing narrative and research.

It’s a book that left me with a handful of major takeaways.

1. The Congressional vote to provide President Bush with the authority to go to war didn’t succeed because those voting had any deep insight or understood the historical import of what they were doing.

The exchanges on the Senate floor offered little of the memorable commentary seen in the two other most recent congressional debates on whether to go to war, in 1991 and in 1964, regarding the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. “The outcome--lopsided support for Bush’s resolution--was preordained,” wrote the Washington Post’s Dana Milbank. Republicans were going to support the president and their party, and Democrats wanted to move on to other issues that would help them more in the midterm elections that at that point were just three weeks away.

As I’ve discovered elsewhere in my journeys through American history, Congress typically passes things--even historic pieces of legislation--because of in-the-moment and historically forgotten political calculations. We say we want our Representatives and Senators to show political courage, to cast the tough votes based on conscience and political ideology, but too often they simply don’t. They vote the way they do because each vote is going to help them or their objectives in the short term. It’s something that I’ve encountered time and time again, and it persists even, as it did for some in Ricks’s account, the failure to stick to principles comes back to bite those who should have shown more courage.

One of those voting for [the authorization] was … Max Cleland, who was in a tight campaign for reelection in which his challenger, Saxby Chambliss, was running commercials that showed images of Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein and implied that Cleland wasn’t standing up to them. Despite his misgivings, Cleland felt under intense political pressure to go with the administration. “It was obvious that if I voted against the resolution that I would be dead meat in the race, just handing them a victory,” he said in 2005. Even so, he now considers his prowar choice “the worst vote I cast.” …

Despite his vote for war, the next month Cleland lost his Senate race by a margin of 53 percent to 46 percent, in part because of a statewide controversy over the Confederate battle flag that helped get out the rural white vote. He said he took it harder than being blown up by a hand grenade in Vietnam. “I went down--physically, mentally, emotionally--down into the deepest, darkest hole of my life,” he recalled. “I had several moments when I just didn’t want to live.”

This should not only be a fundamental lesson for those who find themselves in Congress and who want to make history, it should also be a fundamental lesson for anyone who wants to get any kind of legislation passed. For those in Congress, please, vote your conscience, that’s what we elected you to do. And for the legislators, always downplay the historical importance of your legislation and always schedule the vote when the political facts on the ground are in your favor.

2. Despite this historical reality about how Congress behaves--Congress was especially asleep at the wheel during the Iraq war.

In previous wars, Congress had been populated by hawks and doves. But as war in Iraq loomed it seemed to consist mainly of lambs who hardly made a peep. There were many failures in the American system that led to the war, but the failures in Congress were at once perhaps the most important and the least noticed.

One of the rules of thumb in military operations is that disasters occur not when one or perhaps two things go wrong--which almost any competent leader can handle--but when three or four things go wrong at once. Overcoming such a combination of negative events is a true test of command. Similarly, the Iraq fiasco occurred not just because the Bush administration engaged in sustained self-deception over the threat presented by Iraq and the difficulty in occupying the country, but also because of other major lapses in several major American institutions, from the military establishment and the intelligence community to the media. In each arena, the problems generally were sins of commission--bad planning, bad leadership, bad analysis, or in the case of journalism, bad reported and editing. The role of Congress in this systemic failure was different, because its mistakes were mainly sins of omission. In the months of the run-up to war, Congress asked very few questions, and didn’t offer any challenge to the administration on the lack of postwar planning.

3. The villains in Ricks’s tale are largely the civilians in the upper ranks of the Bush administration.

Primarily Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld...

Ultimately, however, the fault for the lapse in the planning must lie with Rumsfeld, the man in charge. In either case, it is difficult to overstate what a key misstep this lack of strategic direction was--probably the single most significant miscalculation of the entire effort. In war, strategy is the searchlight that illuminates the way ahead. In its absence, the U.S. military would fight hard and well but blindly, and the noble sacrifices of soldiers would be undercut by the lack of thoughtful leadership at the top that soberly assessed the realities of the situation and constructed a response.

Strategic leadership was apparently one of Rumsfeld’s weaker suits. But so was a confused reporting structure that, it seems, even he did not understand.

In a meeting in the White House situation room one day, there was a lot of “grousing” about [Coalition Provisional Authority Chief L. Paul] Bremer, a senior administration official who was there recalled. As the meeting was breaking up [Condoleezza] Rice, the national security adviser, reminded Rumsfeld that Bremer reported to him. “He works for you, Don,” Rice said, according to this official.

“No, he doesn’t,” Rumsfeld responded--incorrectly--this official recalled. “He’s been talking to the NSC, he works for the NSC.”

Bremer relates a similar anecdote in his memoir, saying that Rumsfeld told him later in 2003 that he was “bowing out of the political process,” which apparently meant he was detaching from dealing with Iraq--a breathtaking step for the defense secretary to take after years of elbowing aside the State Department and staffers on the National Security Council.

Speaking of Bremer, he is clearly another civilian villain in Ricks’s tale.

One of the first things Bremer did after arriving in Iraq was show [Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance Chief Jay] Garner the order he intended to issue to rid Iraq if Baathist leadership. “Senior Party Members,” it stated, “are hereby removed from their positions and banned from future employment in the public sector.” In addition, anyone holding a position in the top three management layers of any ministry, government-run corporation, university or hospital and who was a party member--even of a junior rank--would be deemed to be a senior Baathist and so would be fired. What’s more, those suspected of crimes would be investigated and, if deemed a flight risk, would be detained or placed under house arrest.

Garner was appalled. …

If issued as written, the order Bremer was carrying would lead to disaster, Garner thought. He went to see the CIA station chief, whom Garner had seen work well with the military. “This is too hard,” Garner told the CIA officer, who read it and agreed. The two allies went back to Bremer.

“Give us an hour or so to redo this,” Garner asked.

“Absolutely not,” Bremer responded. “I have my instructions, and I am going to issue this.”

The CIA station chief urged Bremer to reconsider. These are the people who know where the levers of the infrastructure are, from electricity to water to transportation, he said. Take them out of the equation and you undercut the operation of this country, he warned.

No, said Bremer.

Okay, the veteran CIA man responded. Do this, he said, but understand one thing: “By nightfall, you’ll have driven 30,000 to 50,000 Baathists underground. And in six months, you’ll really regret this.” ...

Bremer looked at the two. “I have my instructions,” he repeated, according to Garner, though it isn’t clear that he really did, as the policy he was implementing wasn’t what had been briefed to the president. A few months later, the veteran CIA man would leave Baghdad, replaced by a far more junior officer. In the fall of 2005 he would resign from government service.

To hear Ricks tell it, these men, and others like them, had all been placed in positions above their competency levels, and none of them possessed the humility to even try to understand the actual situation on the ground.

There is an interesting passage in Ricks’s account that demonstrates the disastrous and tragic results of Bremer’s decision to “de-Baathify” the country.

At the end of May and in early June [of 2003], dismissed ministry workers and former Iraqi army soldiers [who Bremer also autocratically put out of work] held a series of demonstrations. Some vowed they would violently oppose the U.S. decisions. “All of us will become suicide bombers,” former officer Khairi Jassim told Reuters. The wire service article was distributed at the CPA [the Coalition Provisional Authority] with that quotation highlighted.

“The only thing left for me is to blow myself up in the face of tyrants,” another officer told Al Jazeera.

Bremer insisted he wouldn’t be moved. “We are not going to be blackmailed into producing programs because of threats of terrorism,” he said at a press conference in early June.

The protests continued. On June 18 an estimated two thousand Iraqi soldiers gathered outside the Green Zone to denounce the dissolution decision. Some carried signs that said, PLEASE KEEP YOUR PROMISES. Others threw rocks. “We will take up arms,” Tahseen Ali Hussein vowed in a speech to the demonstrators, according to an account by Agence France Presse. “We are all very well-trained soldiers and we are armed. We will start ambushes, bombings and even suicide bombings. We will not let the Americans rule us in such a humiliating way.” U.S. soldiers fired into the crowd, killing two.

What I find so fascinating about this passage, I think, is the way the two sides are so tragically talking past each other, each using words that mean something quite different in the opposite’s culture.

Please keep your promises, the Iraqis are saying. You are humiliating us.

We will take up arms, the Americans are hearing. We will become suicide bombers. And, as a result, are saying in return, We will not be blackmailed by threats of terrorism.

4. In contrast to these civilian leaders, Ricks portrays many of the military leaders as the pyrrhic heroes of the tale, having done the best they could under the very difficult situations created for them.

And unlike their civilian leaders, they understood the situation on the ground and the people they would come to fight. One shining example is Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Holshek, who took exception to the way his commanding officer was treating the civilian Iraqi population.

He asked his commander to imagine himself the head of a household in an Iraqi village. “Two o’clock in the morning, your door bursts open. A bunch of infantry guys burst into the private space of the house--in a society where family honor is the most important thing--and you lay the man down, and put the plastic cuffs on? And then we say, ‘Oops, wrong home?’ In this society, the guy has no other choice but to seek restitution. He will do that by placing a roadside bomb for one hundred dollars, because his family honor has been compromised, to put it mildly.” Simply to restore his own self-respect, the Iraqi would then have to go out and take a shot at American forces.

What was Colonel Holshek’s preferred method for dealing with these situations?

The wrong doors continued to be smashed on occasion, but when they were, Holshek would issue a letter that stated, “We are sorry for the intrusion, we are trying to help here, and it is a difficult business, and we sometimes make mistakes. If you have information that would help us, we would be grateful.” The cash equivalent in dinars of one hundred dollars would accompany the note. Those gestures of regret didn’t really win over Iraqis, Holshek recalled later, but he said he thought they did tend to tamp down anger, and so curtail acts of revenge.

Because that’s the essential point. Certainly in the beginning, before there was an organized counterinsurgency, and throughout the occupation among certain civilian populations, the attacks on American forces were not acts of terrorism, but those of revenge against aggrieved honor.

[Major Isaiah] Wilson, the historian and 101st planner, later concluded that much of the firing on U.S. troops in the summer and fall of 2003 consisted of honor shots, intended not so much to kill Americans as to restore Iraqi honor. “Honor and pride lie at the center of tribal society,” he wrote. In a society where honor equals power, and power ensures survival, the restoration of damaged honor can be a matter of urgency. But that didn’t mean that Iraqis insulted by American troops necessarily felt they had to respond lethally, Wilson reflected. “Honor that is lost or taken must be returned by the offender, through ritualistic truce sessions, else it will be taken back through force of arms.” In Iraq this sometimes was expressed in ways similar to the American Indian practice of counting coup, in which damaging the enemy wasn’t as important as demonstrating that one could. So, Wilson observed, an Iraqi would take a wild shot with a rocket-propelled grenade, or fire randomly into the air as a U.S. patrol passed. “Often the act of taking a stand against the ‘subject of dishonor’ is enough to restore the honor to the family or tribe,” whether or not the attack actually injured someone, he wrote. “Some of the attacks that we originally saw as ‘poor marksmanship’ likely were intentional misses by attackers pro-progress and pro-U.S., but honor-bound to avenge a perceived wrong that U.S. forces at the time did not know how to appropriately resolve.” But U.S. troops assumed simply that the Iraqis were bad shots.

I find this fascinating, this cultural divide between the Americans and the Iraqis, how it affected the progress of the war, and how few people in the U.S. apparatus seemed to understand the fundamental premise that the people they encountered were simply that--people.

[Captain Oscar Estrada] thought about an incident a few weeks earlier on the road east of Baqubah the soldiers called RPG Alley. The groves of date palms along the road provided insurgents with hiding places from which to fire their rocket-propelled grenades. When a unit ahead of them in a convoy reported taking fire from one such grove, he recalled, everyone began firing--automatic weapons, grenades, and .50 caliber heavy machine guns.

“What the hell are we shooting at?” he had screamed at a buddy as he fired his M-16.

“I’m not sure,” the soldier had responded. “By the shack. You?”

“I’m just shooting where everybody else is shooting,” Estrada had said, continuing to squeeze off rounds.

When the firing ended, he heard the commander on the radio. “Dagger, this is Bravo 6. Do you have anything, over?”

“Roger. … We have a guy here who’s pretty upset. I think we killed his cow, over.”

“Upset how, over?”

“He can’t talk. I think he’s in shock. He looks scared, over.”

“He should be scared. He’s the enemy.”

“Uhm, ahh, roger, 6. … He’s not armed and looks like a farmer or something.”

“He was in the grove that we took fire from. He’s a fucking bad guy.”

A fucking bad guy. We all know what you do when you encounter a bad guy, right? You shoot him. Good guys always shoot the bad guys. It helps keep their sisters and girlfriends safe.

“Roger.”

Estrada wondered what was gained from that minor incident, and what was lost. “Did his family depend on that cow for its survival? Had he seen his world fall apart? Had we lost both his heart and his mind?” Fundamentally, Estrada was asking himself whether the U.S. Army should be in Iraq, and if so, whether it was approaching the occupation of Iraq in the right way. “I was beginning to come to terms with serious doubts about our cause,” he later said, “and whether even if I accepted that our cause was just, our day-to-day actions did anything to champion it.”

After reading Ricks’s book, I find that Captain Estrada is not the only person asking these questions.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Labels:

Books Read

Monday, January 16, 2017

Values Can Take Time to Change Culture

It's been a while since I wrote about core values on this blog, but a thought occurred to me the other day that seemed like it was worth sharing.

My association has a set of core values (long story there; check out this index of posts if interested in reading more) and we now consistently use them in our hiring and on-boarding process. We interview not just for skills but for fit with our values, and we reinforce the importance of finding that fit by assessing the new employee after three months to determine if we got the fit right. We want people in our organization who walk and talk our values, and the 3-month review is an opportunity reinforce that commitment, provide helpful encouragement and feedback, and, if necessary, make a different decision.

We do these things because we believe that the values have the power to change our culture for the better, but only if we take them seriously in the hiring and on-boarding processes of the organization.

But here's the thought that occurred to me. Given the relative small size and stability of our organization, any culture change that results from this commitment to our values is going to take some time to manifest itself. Time not as in weeks and months, but more likely time as in years.

If you're looking for culture change solely as a result of baking your values into your hiring and on-boarding process, then by definition you'll need to do a lot of hiring and on-boarding before you can expect to see a lot of culture change as a result. If you have only a handful of staff positions, and only fraction of those turn over with any regularity, you'll have to find other mechanisms for those values to work their culture change potential on your organization.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://tylermayforth.com/flipping-the-calendar-from-2015-to-2016/

My association has a set of core values (long story there; check out this index of posts if interested in reading more) and we now consistently use them in our hiring and on-boarding process. We interview not just for skills but for fit with our values, and we reinforce the importance of finding that fit by assessing the new employee after three months to determine if we got the fit right. We want people in our organization who walk and talk our values, and the 3-month review is an opportunity reinforce that commitment, provide helpful encouragement and feedback, and, if necessary, make a different decision.

We do these things because we believe that the values have the power to change our culture for the better, but only if we take them seriously in the hiring and on-boarding processes of the organization.

But here's the thought that occurred to me. Given the relative small size and stability of our organization, any culture change that results from this commitment to our values is going to take some time to manifest itself. Time not as in weeks and months, but more likely time as in years.

If you're looking for culture change solely as a result of baking your values into your hiring and on-boarding process, then by definition you'll need to do a lot of hiring and on-boarding before you can expect to see a lot of culture change as a result. If you have only a handful of staff positions, and only fraction of those turn over with any regularity, you'll have to find other mechanisms for those values to work their culture change potential on your organization.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://tylermayforth.com/flipping-the-calendar-from-2015-to-2016/

Labels:

Associations,

Core Values

Monday, January 9, 2017

You Can Decide When To Check Your Email

A post on Associations Now about a new law that gives French employees the right to ignore emails sent during hours that they’re off the clock caught my eye this week. It's evidently a godsend to France's stressed-out workers who, according to a quoted member of the French parliament, physically leave the office at the end of each workday, but "remain attached [to their offices] by a kind of electronic leash—like a dog.”

I sympathize. But at the risk of sounding old and elitist, why on earth is anyone still checking their email at any time other than when they decide to check their email?

Let me share a story. When I was a kid, like many in my generation, the house I grew up in had a telephone affixed to the kitchen wall (ours was green) with a long, kinky cord that would allow the user to wander through half the house while talking on it. When that phone rang, it was an event. Family members leapt off the sofa or out of kitchen chairs in a race to see who would get the privilege of answering that phone. The phone is ringing! Someone is calling! It must be important!

Now, of course, that's ancient history. Phones--or more properly, the phone function on the little computers we call smartphones--are infrequently used. Unless your livelihood depends on cold call sales, most phone calls are nuisances, interruptions to the productive flow of our work, things to be avoided.

For a while, email did take the place of that kitchen phone with the kinky cord. In it's heyday, every email was important and came with the expectation of an instant response. The ringing phone got replaced with AOL's "You've Got Mail!" voice, and it demanded our attention,

But those days, too, have passed. Email remains a productivity tool, but it is so clouded with spam, blind-copied irrelevancies, and unsubscribed-for newsletters that it's no longer possible to treat every message as an event. Or, frankly, for anyone to have the expectation that the person on the other end of the send button will do so.

Here's how I look at it. Email is an asynchronous method for disseminating information or advancing projects. You send and you get replies. You get messages and you reply to them. But none of that happens in real time. It happens over a period of days. It's supposed to happen over a period of days. As odd as it may sound given our history on this subject, if you need a response to something sooner than that, you're better off picking up the phone--or sending a text.

So, please, if there is anyone out there who still needs to be granted permission, I'll grant it. You have the power to decide when to check and respond to your emails. Stop leaping off the sofa every time a new message comes in.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://bigarcreative.com/from-inbox-to-home-screen-how-to-get-your-emails-opened/

I sympathize. But at the risk of sounding old and elitist, why on earth is anyone still checking their email at any time other than when they decide to check their email?

Let me share a story. When I was a kid, like many in my generation, the house I grew up in had a telephone affixed to the kitchen wall (ours was green) with a long, kinky cord that would allow the user to wander through half the house while talking on it. When that phone rang, it was an event. Family members leapt off the sofa or out of kitchen chairs in a race to see who would get the privilege of answering that phone. The phone is ringing! Someone is calling! It must be important!

Now, of course, that's ancient history. Phones--or more properly, the phone function on the little computers we call smartphones--are infrequently used. Unless your livelihood depends on cold call sales, most phone calls are nuisances, interruptions to the productive flow of our work, things to be avoided.

For a while, email did take the place of that kitchen phone with the kinky cord. In it's heyday, every email was important and came with the expectation of an instant response. The ringing phone got replaced with AOL's "You've Got Mail!" voice, and it demanded our attention,

But those days, too, have passed. Email remains a productivity tool, but it is so clouded with spam, blind-copied irrelevancies, and unsubscribed-for newsletters that it's no longer possible to treat every message as an event. Or, frankly, for anyone to have the expectation that the person on the other end of the send button will do so.

Here's how I look at it. Email is an asynchronous method for disseminating information or advancing projects. You send and you get replies. You get messages and you reply to them. But none of that happens in real time. It happens over a period of days. It's supposed to happen over a period of days. As odd as it may sound given our history on this subject, if you need a response to something sooner than that, you're better off picking up the phone--or sending a text.

So, please, if there is anyone out there who still needs to be granted permission, I'll grant it. You have the power to decide when to check and respond to your emails. Stop leaping off the sofa every time a new message comes in.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://bigarcreative.com/from-inbox-to-home-screen-how-to-get-your-emails-opened/

Labels:

Associations,

Leadership

Saturday, January 7, 2017

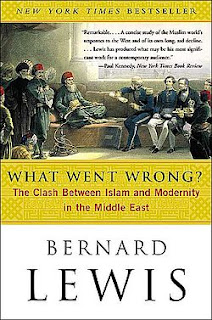

What Went Wrong? by Bernard Lewis

The subtitle here is “The Clash Between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East,” and that’s a far more descriptive title for this book than “What Went Wrong?”, which seems to imply that the author has posed a question he intends to answer.

Which he doesn’t.

Or, to be more precise, at first appears to, but then comes on stage to undercut the argument he has been making and to state unequivocally that the answer he appears to have given is not the answer, and the proceeds to leave the question unanswered at the end.

A frustrating read, easily avoided if they had simply chosen a better title.

The question, maybe not obviously phrased as “What Went Wrong?”, may be better stated as “Why is the Islamic World, once the dominant scientific and cultural force on the planet, now so backward and repressive when compared to the West?” And the answer Lewis appears to offer throughout the analysis and discussion of his first 150 pages seems both tragic and simple.

It’s Islam. The reason the Islamic World is no longer the dominant scientific and cultural force on the planet is because it is Islamic. Islam couldn't keep pace with other frames of thought and culture.

To be honest, it is an answer I didn't expect and wasn't much prepared to believe. Surely, I thought, the question has a more complex answer than that. And Lewis himself seems just as uncomfortable with that answer, stepping up here in his conclusion to refute the conclusion his own preceding text had convinced me of.

For most of the Middle Ages, it was neither the older cultures of the Orient nor the newer cultures of the West that were the major centers of civilization and progress, but the world of Islam in the middle. It was there that old sciences were recovered and developed and new sciences created; there that new industries were born and manufactures and commerce expanded to a level previously without precedent. It was there, too, that governments and societies achieved a degree of freedom of thought and expression that led persecuted Jews and even dissident Christians to flee for refuge from Christendom to Islam. The medieval Islamic world offered only limited freedom in comparison with modern ideals and even with modern practice in the more advanced democracies, but it offered vastly more freedom than any of its predecessors, its contemporaries and most of its successors.

The point has often been made--if Islam is an obstacle to freedom, to science, to economic development, how is it that Muslim society in the past was a pioneer of all three, and this when Muslims were much closer in time to the sources and inspiration of their faith than they are now? Some have indeed posed the question in a different form--not “What has Islam done to the Muslims?” but “What have the Muslims done to Islam?”, and have answered by laying blame on specific teachers and doctrines and groups.

For those nowadays known as Islamists or fundamentalists, the failures and shortcomings of the modern Islamic lands afflicted them because they adopted alien notions and practices. They fell away from authentic Islam, and thus lost their former greatness. Those known as modernists or reformers take the opposite view, and see the cause of this loss not in the abandonment but in the retention of the old ways, and especially in the inflexibility and ubiquity of the Islamic clergy. These, they say, are responsible for the persistence of beliefs and practices that might have been creative and progressive a thousand years ago, but are neither today. Their usual tactic is not to denounce religion as such, still less Islam in particular, but to level their criticism against fanaticism. It is to fanaticism, and more particularly to fanatical religious authorities, that they attribute the stifling of the once great Islamic scientific movement, and, more generally, of freedom of thought and expression.

Lewis then goes on to present several more diagnostic views on the subject, eventually throwing so many cooks in the kitchen that his “conclusion” lacks any concluding thought or thesis at all. What Went Wrong? Who can say? Lewis seems to say. Lots of people certainly have lots of different ideas.

But go back and read these last excerpted paragraphs again. I think the answer we seek is in there, whether or not Lewis wants to claim it as his own. Medieval Islam offered limited freedom in comparison to modern democracies, but more freedom when compared to its contemporaries in the Orient and in the West. Might not that mean that societies based on Islam were able to reach a higher peak of freedom than those based on Christianity, but ultimately a lower one than those based on individual liberty and democracy?

For the sake of the thought experiment, assign each kind of society a “freedom score” between 1 and 10, with 10 being the mark for absolute individual liberty and 1 being the mark for absolute state (and/or religious) control. As societies grow and mature, they have the ability to “improve” their score, but each has an inherent limit, associated with its intrinsic values and ideals. Medieval Christianity, for example, might achieve a maximum score of 3, while Medieval Islam might achieve as high as a 5, consistently able to stay ahead of any Christian-based society in the freedom department.

But change those Christian-based societies in the direction of liberal democracies--as began to happen after the Renaissance--and they now have a maximum freedom score of 7, and the ability to start climbing the ladder towards that position. Islamic societies, given their values and ideals, can still never go above a 5, so those previously Christian societies (now, importantly, no longer such) can begin to outpace them and take their place as the world’s leaders in freedom, science, and economic development.

This makes some level of sense to me, although I’m sure it has a number of flaws any reasonably-educated sociologist or historian would detect. (It still, admittedly, doesn’t answer the question why Christian societies were able to turn towards classical liberalism and Islamic societies weren’t.) But throughout much of the Golden Age of Islamic society that Lewis documents in this book, we see a subservience to a strict interpretation of Islam and a hostility to thoughts and actions that fall outside that single spectrum that would seem to support my hypothesis.

These societies, it seemed, kept to themselves as much as possible, believing that they had little to learn from “Christian” lands.

To preach a return to authentic, pristine Islam was one thing; to seek the answer in Christian ways or ideas was another--and, according to the notions of the time, self-evidently absurd. Muslims were accustomed to regard Christianity as an earlier, corrupted version of the true faith of which Islam was the final perfection. One does not go forward by going backward. There must therefore be some circumstance other than religion or culture, which is part of religion, to account for the otherwise unaccountable superiority achieved by the Western world. A Westerner at the time--and many Muslims at the present day--might suggest science and the philosophy that sustains it. This view would not have occurred to those from whom philosophy was the handmaiden of theology and science merely a collection of pieces of knowledge and of devices.

It’s a neat little trap, isn’t it? Your culture teaches you that there is no separation between religion, philosophy, and science--one flowing inexorably from the one before, and if one reveals anything contrary to its preceding precepts, it must be in error. The earth can’t go around the sun because God made the sun stand still in the heavens. And yet, while your culture operates on this premise, it is surrounded by cultures that are slowly reversing that ideological order. Science first, then philosophy, and then religion. With your vision clouded by religious revelation, those other cultures begin to surpass you in scientific and sociological achievements. And when they confront you in a way you can’t avoid--on the battlefield, let’s say--you can’t explain their success in any other way than by calling them infidels and barbarians. Indeed, perhaps the Devil helped them defeat you? How does a culture so oriented get out of that trap? The solution isn’t in their holy books.

And indeed, Lewis documents that as these “surrounding” cultures became increasingly less Christian and increasingly more enlightened, benefiting and advancing in the areas of knowledge and science, their expertise did translate to the art of war. And the Islamic societies truly began to confront their own inferiority when they found themselves losing consistently and decisively to these “Christian” neighbors on the battlefield. Some even tried to do something about it. But there was a problem.

Clearly new measures were needed to meet these new threats, and some of them violated accepted Islamic norms. The leaders of the ulema, the doctors of the Holy Law, were therefore asked, and agreed, to authorize two basic changes. The first was to accept infidel teaching and give them Muslim pupils, an innovation of staggering magnitude in a civilization that for more than a millennium had been accustomed to despise the outer infidels and barbarians as having nothing of any value to contribute, except perhaps themselves as raw material for incorporation in the domains of Islam and conversion to the faith of Islam.

The second change was to accept infidel allies in their wars against other infidels.

But even in these dealings, the Muslims would not treat their “infidel” allies as equals, expecting them, as one letter Lewis cites from the Sultan of Turkey to Queen Elizabeth of England describes, to be…

...“loyal and firm-footed in the path of vassalage and obedience … and to manifest loyalty and subservience” to the Ottoman throne.

This clearly would not work and did not work. And just as quickly, it seems, these Islamic societies abandoned the experiment with these new ideas. They were too dangerous and threatening to the basic principles of their faith. By the time Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, bringing the Western attitudes and ideas of the French Revolution to cloistered Muslims, outright rejection seemed the only appropriate course of action.

A proclamation was therefore prepared and distributed both in Turkish and in Arabic throughout the Ottoman lands, refuting the doctrines of revolutionary France. It begins: “...In the name of God, the merciful and the compassionate. O you who believe in the oneness of God, community of Muslims, know that the French nation (may God devastate their dwellings and abase their banners) are rebellious infidels and dissident evildoers. They do not believe in the oneness of the Lord of Heaven and Earth, nor in the mission of the intercessor on the Day of Judgement, but have abandoned all religions and denied the afterworld and its penalties. They do not believe in the Day of Resurrection and pretend that only the passage of time destroys us and that beyond this there is no resurrection and no reckoning, no examination and no retribution, no question and no answer.”

Not exactly a Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, is it? The founding values of this French society--still not perfect in the eyes any modern liberal democracy--are not, to the suzerain of Egypt that issued this proclamation, an alternate construction for society. They are rebelliously infidel and a dissident evil.

But by this time, it was too late to even try to catch up.

Later attempts to catch up with the Industrial Revolution fared little better. Unlike the rising powers of Asia, most of which started from a lower economic base than the Middle East, the countries in the region still lag behind in investment, job creation, productivity, and therefore in exports and incomes. According to a World Bank estimate, the total exports of the Arab world other than fossil fuels amount to less than those of Finland, a country of five million inhabitants. Nor is much coming into the region by way of capital investment. On the contrary, wealthy Middle Easterners prefer to invest their capital abroad, in the developed world.

Despite myself, as I continued to read this particular excerpt, I found myself surprised by Lewis’s apparent contention that certain elements of progressive, pluralistic societies were now simply beyond the vision of many Islamic societies.

The other immediately visible difference between Islam and the West was in politics and more particularly in administration. Already in the eighteenth century ambassadors to Berlin and Vienna, later to Paris and London, describe--with wonderment and sometimes with admiration--the functioning of an efficient bureaucratic administration in which appointment and promotion are by merit and qualification rather than by patronage and favor, and recommend the adoption of something similar.

The impact of Western example and Western ideas also brought new definitions of identity and consequently new allegiances and aspirations. Two ideas were especially important, both new in a culture where identity was basically religious and allegiance normally dynastic. The first was that of patriotism, coming from Western Europe, particularly from France and England, and favored by the younger Ottoman elites, who saw in an Ottoman patriotism a way of binding together the heterogeneous populations of the empire in a common love of country expressed in a common allegiance to its ruler. The second, from Central and Eastern Europe, was nationalism, a more ethnic and linguistic definition of identity, the effect of which in the Ottoman political community was not to unify but to divide and disrupt.

Efficient bureaucracies based on merit, patriotism, nationalism--these are all concepts evidently foreign to the Islamic world, not because its people are incapable of understanding them and seeing their benefits (the Islamic ambassadors and Ottoman elites evidently did), but as a result, it seems, of that world’s alignment and fealty to the principles of Islam.

Lewis relays anecdote after anecdote, throughout a long history of Muslim domination, of Islamic scholars and ambassadors correctly diagnosing the things that helped the rest of the world rise so far above the achievements of their home countries.

An important figure in the introduction and dissemination of these ideas was Sadik rifat Pasha (1807-1856), who drafted a memorandum on reform while he was Ottoman ambassador in Vienna in 1837 and in close touch with Prince Metternich. Like most other Middle Eastern visitors, Sadik Rifat Pasha was greatly impressed by European progress and prosperity and saw in the adoption and adaptation of these the best means of regenerating his own country. European wealth, industry, and science, he explains, are the result of certain political conditions, ensuring stability and tranquility. These in turn depend on “the attainment of complete security for the life, property, honor and reputation of each nation and people, that is to say, on the proper application of the necessary rights of freedom.

And later, as European colonization began to take over, these lessons began to be understood by more than just the intellectuals and elite travelers.

The West European empires, by the very nature of the culture, the institutions, even the languages that they brought with them and imposed on their colonial subjects, demonstrated the ultimate incompatibility of democracy and empire, and sealed the doom of the own domination. They taught their subjects English, French, and Dutch because they needed clerks in their offices and counting houses. But once these subjects had mastered a Western European language, as did increasing numbers of Muslims in Western-dominated Asia and Africa, they found a new world open to them, full of new and dangerous ideas such as political freedom and national sovereignty and responsible government by the consent of the governed.

After all this analysis, Lewis may not want to draw the conclusion that Islam is to blame, but I would forgive any of his readers who might feel justified in jumping to it. What other force was there at work in these countries that consistently saw things like political freedom, national sovereignty and responsible government by the consent of the governed as dangerous ideas? From where I sit, the leap to the “Islam to blame” conclusion is one across a very narrow chasm.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Which he doesn’t.

Or, to be more precise, at first appears to, but then comes on stage to undercut the argument he has been making and to state unequivocally that the answer he appears to have given is not the answer, and the proceeds to leave the question unanswered at the end.

A frustrating read, easily avoided if they had simply chosen a better title.

The question, maybe not obviously phrased as “What Went Wrong?”, may be better stated as “Why is the Islamic World, once the dominant scientific and cultural force on the planet, now so backward and repressive when compared to the West?” And the answer Lewis appears to offer throughout the analysis and discussion of his first 150 pages seems both tragic and simple.

It’s Islam. The reason the Islamic World is no longer the dominant scientific and cultural force on the planet is because it is Islamic. Islam couldn't keep pace with other frames of thought and culture.

To be honest, it is an answer I didn't expect and wasn't much prepared to believe. Surely, I thought, the question has a more complex answer than that. And Lewis himself seems just as uncomfortable with that answer, stepping up here in his conclusion to refute the conclusion his own preceding text had convinced me of.

For most of the Middle Ages, it was neither the older cultures of the Orient nor the newer cultures of the West that were the major centers of civilization and progress, but the world of Islam in the middle. It was there that old sciences were recovered and developed and new sciences created; there that new industries were born and manufactures and commerce expanded to a level previously without precedent. It was there, too, that governments and societies achieved a degree of freedom of thought and expression that led persecuted Jews and even dissident Christians to flee for refuge from Christendom to Islam. The medieval Islamic world offered only limited freedom in comparison with modern ideals and even with modern practice in the more advanced democracies, but it offered vastly more freedom than any of its predecessors, its contemporaries and most of its successors.

The point has often been made--if Islam is an obstacle to freedom, to science, to economic development, how is it that Muslim society in the past was a pioneer of all three, and this when Muslims were much closer in time to the sources and inspiration of their faith than they are now? Some have indeed posed the question in a different form--not “What has Islam done to the Muslims?” but “What have the Muslims done to Islam?”, and have answered by laying blame on specific teachers and doctrines and groups.

For those nowadays known as Islamists or fundamentalists, the failures and shortcomings of the modern Islamic lands afflicted them because they adopted alien notions and practices. They fell away from authentic Islam, and thus lost their former greatness. Those known as modernists or reformers take the opposite view, and see the cause of this loss not in the abandonment but in the retention of the old ways, and especially in the inflexibility and ubiquity of the Islamic clergy. These, they say, are responsible for the persistence of beliefs and practices that might have been creative and progressive a thousand years ago, but are neither today. Their usual tactic is not to denounce religion as such, still less Islam in particular, but to level their criticism against fanaticism. It is to fanaticism, and more particularly to fanatical religious authorities, that they attribute the stifling of the once great Islamic scientific movement, and, more generally, of freedom of thought and expression.

Lewis then goes on to present several more diagnostic views on the subject, eventually throwing so many cooks in the kitchen that his “conclusion” lacks any concluding thought or thesis at all. What Went Wrong? Who can say? Lewis seems to say. Lots of people certainly have lots of different ideas.

But go back and read these last excerpted paragraphs again. I think the answer we seek is in there, whether or not Lewis wants to claim it as his own. Medieval Islam offered limited freedom in comparison to modern democracies, but more freedom when compared to its contemporaries in the Orient and in the West. Might not that mean that societies based on Islam were able to reach a higher peak of freedom than those based on Christianity, but ultimately a lower one than those based on individual liberty and democracy?

For the sake of the thought experiment, assign each kind of society a “freedom score” between 1 and 10, with 10 being the mark for absolute individual liberty and 1 being the mark for absolute state (and/or religious) control. As societies grow and mature, they have the ability to “improve” their score, but each has an inherent limit, associated with its intrinsic values and ideals. Medieval Christianity, for example, might achieve a maximum score of 3, while Medieval Islam might achieve as high as a 5, consistently able to stay ahead of any Christian-based society in the freedom department.

But change those Christian-based societies in the direction of liberal democracies--as began to happen after the Renaissance--and they now have a maximum freedom score of 7, and the ability to start climbing the ladder towards that position. Islamic societies, given their values and ideals, can still never go above a 5, so those previously Christian societies (now, importantly, no longer such) can begin to outpace them and take their place as the world’s leaders in freedom, science, and economic development.

This makes some level of sense to me, although I’m sure it has a number of flaws any reasonably-educated sociologist or historian would detect. (It still, admittedly, doesn’t answer the question why Christian societies were able to turn towards classical liberalism and Islamic societies weren’t.) But throughout much of the Golden Age of Islamic society that Lewis documents in this book, we see a subservience to a strict interpretation of Islam and a hostility to thoughts and actions that fall outside that single spectrum that would seem to support my hypothesis.

These societies, it seemed, kept to themselves as much as possible, believing that they had little to learn from “Christian” lands.

To preach a return to authentic, pristine Islam was one thing; to seek the answer in Christian ways or ideas was another--and, according to the notions of the time, self-evidently absurd. Muslims were accustomed to regard Christianity as an earlier, corrupted version of the true faith of which Islam was the final perfection. One does not go forward by going backward. There must therefore be some circumstance other than religion or culture, which is part of religion, to account for the otherwise unaccountable superiority achieved by the Western world. A Westerner at the time--and many Muslims at the present day--might suggest science and the philosophy that sustains it. This view would not have occurred to those from whom philosophy was the handmaiden of theology and science merely a collection of pieces of knowledge and of devices.