When in a negotiation of any kind, it's important to understand the time horizon that each party is bringing into the discussion. Because the one with the longer time horizon will have an advantage over the one with the shorter one.

If you need a resolution sooner than that of your negotiating partner, you will be forced to make decisions from a more limited set of options. Whatever the reason for the shorter horizon--fewer resources, less support from your leadership, more competing priorities--the implicit need to get the deal done will close off avenues of approach that may be readily acceptable to the partner across the table. They, compared to you, will have the luxury of time. Next week, next month, next year--it won't change their bottom line but it will have a dramatic effect on yours.

For this and several other reasons, it's always preferable to be the party with the longer time horizon in an negotiation. The ability to play the long game grants tremendous strategic advantages and allows for the consideration of far more variables.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

https://kasina.com/blog/2014/07/compensate-dc-wholesalers-for-long-game.html

Monday, February 27, 2017

Monday, February 20, 2017

Not Everyone Will Agree With Your Vision

And I know I've written before about how difficult that can be. Sometimes the way forward isn't at all clear, even to the leader, and sometimes he or she forgets how important it is to communicate it over and over again. Especially when the vision requires the organization or the people within it to change, communicating the vision once is never enough. It has to be communicated and re-communicated time and time again, else forces conscious and unconscious within the organization will drift back towards the status quo.

But sometimes, even leaders who have communicated their vision, and have re-communicated it multiple times, will find themselves in situations where they themselves will question whether or not the vision has to be re-communicated again. Seriously, they may think. We've talked about this five or six times already. Do I have to spell this out again? What are you not getting?

If you find yourself in this situation, recognize that it is a warning sign. And the challenge before you is to figure out what the nature of the warning is.

First, as repetitive as the action may seem, take a step back and reflect. Is this another opportunity to communicate your vision? To clarify what it is the organization is trying to achieve and what the essential steps to getting there are? Resistance to change is tenacious, and it is not always willful and disloyal. It never hurts to reinforce what is required and what your expectations are.

But after you've done that, you need to spend some time thinking about the true nature of the obstacle before you. As much as you may not want to admit it, there can be people, both in and out of the organization, who will oppose your vision. After all your communications, they will understand where you are leading the organization, but they will still disagree with it. They will quite simply think you are wrong, and that the old way or their own way is the better way.

What you do in these situations can be one of the most difficult tests of your leadership. When I'm confronted with such a situation, I usually ask myself where my greater loyalties lie--with the vision, or with the relationship that I've built.

The answer isn't always be the same. My vision doesn't always win, but my future actions will be governed by whichever answer I come up with. Sometimes, it is impossible to save both the vision and the relationship, and one has to be sacrificed for the other.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://dwbassociates.com/blog/index.php/how-to-effectively-communicate-your-vision-statement/

Labels:

Associations,

Leadership

Saturday, February 18, 2017

The Razor’s Edge by W. Somerset Maugham

I have to admit that I was a little disappointed with this one. Generally speaking, Maugham is one of my favorite authors, and I can usually find something of enduring value in his novels and short stories. I struggled with that in The Razor’s Edge, primarily, I think, because I didn’t know who I was supposed to be paying attention to. I may need to read it again.

Read any summary of the novel--and there are many out there--and you will assume that it is a story about Larry Darrell, an American returned and traumatized by the First World War, who decides to reject the comforts and customs of his social position in order to find answers to the transcendental questions of existence.

“I’ve been reading Spinoza the last month or two. I don’t suppose I understand very much of it yet, but it fills me with exultation. It’s like landing from your plane on a great plateau in the mountains. Solitude, and an air so pure that it goes to your head like wine and you feel like a million dollars.”

“When are you coming back to Chicago?”

“Chicago? I don’t know. I haven’t thought of it.”

“You said that if you hadn’t got what you wanted after two years you’d give it up as a bad job.”

“I couldn’t go back now. I’m on the threshold. I see vast lands of the spirit stretching out before me, beckoning, and I’m eager to travel them.”

“What do you expect to find in them?”

“The answers to my questions.” He gave her a glance that was almost playful, so that except that she knew him so well, she might have thought he was speaking in jest. “I want to make up my mind whether God is or God is not. I want to find out why evil exists. I want to know whether I have an immortal soul or whether when I die it’s the end.”

This is a dialogue Larry has with his then-fiancee Isabel Bradley, who has agreed to let him live in France for the two years mentioned, to see, from her point of view, if he can get over the funk he has found himself in, come back to America to marry her and begin a career as a stockbroker in a prestigious firm.

A very respectable and proper set of expectations. But totally in conflict with Larry’s true aims, described, I suppose it should be parenthetically mentioned, in a set of themes and images that are eerily reminiscent of Hugh Conway in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, a 1933 novel I can only assume Maugham read before publishing The Razor’s Edge in 1944.

But, let’s get back to Isabel and Larry.

Isabel gave a little gasp. It made her uncomfortable to hear Larry say such things, and she was thankful that he spoke so lightly, in the tone of ordinary conversation, that it was possible for her to overcome her embarrassment.

“But Larry,” she smiled. “People have been asking those questions for thousands of years. If they could be answered, surely they’d have been answered by now.”

Larry chuckled.

“Don’t laugh as if I’d said something idiotic,” she said sharply.

“On the contrary I think you’ve said something shrewd. But on the other hand you might say that if men have been asking them for thousands of years it proves that they can’t help asking them and have to go on asking them. Besides, it’s not true that no one has found the answers. There are more answers than questions, and lots of people have found answers that were perfectly satisfactory for them. Old Ruysbroeck for instance.”

“Who was he?”

“Oh, just a guy I didn’t know at college,” Larry answered flippantly.

Isabel didn’t know what he meant, but passed on.

“It all sounds so adolescent to me. Those are the sort of things sophomores get excited about and then when they leave college they forget about them. They have to earn a living.”

They have to earn a living. Hark that. A major theme is developing there.

“I don’t blame them. You see, I’m in the happy position that I have enough money to live on. If I hadn’t I’d have had to do like everybody else and make money.”

“But doesn’t money mean anything to you?”

“Not a thing,” he grinned.

“How long d’you think all this is going to take you?”

“I wouldn’t know. Five years. Ten years.”

“And after that? What are you going to do with all this wisdom?”

“If I ever acquire wisdom I suppose I shall be wise enough to know what to do with it.”

Wisdom is only useful if one can “do” something with it. The theme continues to develop.

Isabel clasped her hands passionately and leant forward in her chair.

“You’re so wrong, Larry. You’re an American. Your place isn’t here. Your place is in America.”

Uh oh. Here it comes.

“I shall come back when I’m ready.”

“But you’re missing so much. How can you bear to sit here in a backwater just when we’re living through the most wonderful adventure the world has ever known? Europe’s finished. We’re the greatest, the most powerful people in the world. We’re going forward by leaps and bounds. We’ve got everything. It’s your duty to take part in the development of your country. You’ve forgotten, you don’t know how thrilling life is in America today. Are you sure you’re not doing this because you haven’t the courage to stand up to the work that’s before every American now? Oh, I know you’re working in a way, but isn’t it just an escape from your responsibilities? Is it more than just a sort of laborious idleness? What would happen to America if everyone shirked as you’re shirking?

And there it is. Probably as fully on display as Maugham dared to make it. In this one scene, we seem to have set before us the dramatic tension that will consume the rest of the narrative. Larry, representing the inner drive for spiritual truth and meaning, and Isabel, representing the cultural drive for wealth and domination, in conflict with one another, in society, and in Maugham’s soul. A reader should be excused for thinking that whichever character achieves happiness in the end will reveal Maugham’s bias in this eternal struggle.

Except, much of the novel isn’t actually about Larry Darrell. Much--too much, in my opinion--is about the petty obsessions that go with wealth and privilege. It’s typified by Isabel Bradley herself in an aspiring upper class kind of way, but even more fully developed in the character of an American expatriate living in Paris named Elliott Templeton.

If I have given the reader an impression that Elliott Templeton was a despicable character I have done him an injustice.

Those, of course, are Maugham’s words, not mine, and they come early, after several pages of character sketch and backstory, in which the author basically describes Templeton as a snob, a phony, and a gold digger.

He was for one thing what the French call serviable, a word for which, so far as I know, there is no exact equivalent in English. The dictionary tells me that serviceable in the sense of helpful, obliging, and kind is archaic. That is just what Elliott was. He was generous, and though early in his career he had doubtless showered flowers, candy, and presents on his acquaintance from an ulterior motive, he continued to do so when it was no longer necessary. It caused him pleasure to give. He was hospitable. His chef was as good as any in Paris and you could be sure at his table of having set before you the earliest delicacies of the season. His wine proved the excellence of his judgment. It is true that his guests were chosen for their social importance rather than because they were good company, but he took care to invite at least one or two for their powers of entertainment, so that his parties were almost always amusing. People laughed at him behind his back and called him a filthy snob, but nevertheless accepted his invitations with alacrity.

He is, I realized, having recently read a biography of Somerset Maugham, clearly patterned after Maugham himself--at least the Maugham who publicly resided in the South of France and entertained aristocrats and celebrities at his villa. Which is odd, of course, because Maugham himself is famously the first-person narrator of The Razor’s Edge. “I have never begun a novel with more misgiving,” the novel begins, and from those first words to the novel’s last, the presence of Maugham--as a character, as the narrator, as an author; or, indeed, as all three--is hopelessly intertwined.

So what is Maughan doing here? He’s hiding, clearly. Obviously in the narrator/character of Maugham, and less obviously in the character of Elliott Templeton. But I believe both of those are really meant just to keep you off the scent. Because Maugham, I suspect, is hiding most deeply of all in the character of Larry Darrell.

“It doesn’t surprise me that you don’t understand Larry,” I said, “because I’m pretty sure he doesn’t understand himself. If he’s reticent about his aims it may be that it’s because they’re obscure to him. Mind you, I hardly know him and this is only guesswork: isn’t it possible that he’s looking for something, but what it is he doesn’t know, and perhaps he isn’t even sure it’s there? Perhaps whatever it is that happened to him during the war has left him with a restlessness that won’t let him be. Don’t you think he may be pursuing an ideal that is hidden in a cloud of unknowing--like an astronomer looking for a star that only a mathematical calculation tells him exists?”

This is Maugham the character/narrator speaking to Isabel, but it is also Maugham the author speaking to the reader, revealing a dangerous truth that perhaps everything he has done, all the works he has written, have been in service of an ideal that he doesn’t know for sure is even there.

This is an exciting interpretation. And it probably requires another full read of the novel if I intend to develop it--here on my blog, or in one of those wistful PhD dissertations I actually think I may have time to write someday.

For example, when I complain that there is too much Elliott Templeton and not enough Larry Darrell in the novel, is that also Maugham telling me something about himself? Is he saying that he regrets all the time he has spent being like Templeton and longs, late in his life, for more of that time having been spent being like Larry?

And then, inevitably, we’ll have to deal with Charles Strickland.

“...What I’m trying to tell you is that there are men who are possessed by an urge so strong to do some particular thing that they can’t help themselves, they’ve got to do it. They’re prepared to sacrifice everything to satisfy their yearning.”

“Even the people who love them?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Is that anything more than plain selfishness?”

“I wouldn’t know,” I smiled.

The smile is the dead giveaway, for our course Maugham--Maugham the author, but here, even Maugham the character/narrator--does know. He, both of them, had already famously written about just such a character--and another of his alter egos.

Here’s how the second paragraph of The Razor’s Edge begins:

Many years ago I wrote a novel called The Moon and Sixpence. In that I took a famous painter, Paul Gauguin, and, using the novelist’s privilege, devised a number of incidents to illustrate the character I had created on the suggestions afforded me by the scanty facts I knew about the French artist. In the present book I have attempted to do nothing of the kind. I have invented nothing. To save embarrassment to people still living I have given to the persons who play a part in this story names of my own contriving, and I have in other ways taken pains to make sure that no one should recognize them.

Maugham’s painter in The Moon and Sixpence, Charles Strickland, is also a man “possessed by an urge so strong to do some particular thing”--paint--that he can’t help himself. He sacrifices everything to satisfy his yearning, even the people who love him. But Maugham, I think, goes out of his way to show that this isn’t plain selfishness. It is, he fears, the only way an artist can bring something great into the world.

In the exchange I most recently cited, Isabel is complaining to Maugham about Larry’s desire to learn Greek.

“What can be the possible use of Larry’s learning dead languages?”

“Some people have a disinterested desire for knowledge. It’s not an ignoble desire.”

“What’s the good of knowledge if you’re not going to do anything with it?”

“Perhaps he is. Perhaps it will be sufficient satisfaction merely to know, as it’s sufficient satisfaction to an artist to produce a work of art. And perhaps it’s only a step toward something further.”

The comparison to art is, I think, significant. If Larry Darrell is a kinder and gentler version of Charles Strickland, then he is much more deeply buried in a text preoccupied with the social graces and appearances that both rejected. In The Moon and Sixpence, Maugham fully embraced the misanthrope within. In The Razor’s Edge, he has screened that creature behind several layers of his own better sensibilities and those of most of us who find themselves approaching the text.

As I said, I think I need to read it again.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Read any summary of the novel--and there are many out there--and you will assume that it is a story about Larry Darrell, an American returned and traumatized by the First World War, who decides to reject the comforts and customs of his social position in order to find answers to the transcendental questions of existence.

“I’ve been reading Spinoza the last month or two. I don’t suppose I understand very much of it yet, but it fills me with exultation. It’s like landing from your plane on a great plateau in the mountains. Solitude, and an air so pure that it goes to your head like wine and you feel like a million dollars.”

“When are you coming back to Chicago?”

“Chicago? I don’t know. I haven’t thought of it.”

“You said that if you hadn’t got what you wanted after two years you’d give it up as a bad job.”

“I couldn’t go back now. I’m on the threshold. I see vast lands of the spirit stretching out before me, beckoning, and I’m eager to travel them.”

“What do you expect to find in them?”

“The answers to my questions.” He gave her a glance that was almost playful, so that except that she knew him so well, she might have thought he was speaking in jest. “I want to make up my mind whether God is or God is not. I want to find out why evil exists. I want to know whether I have an immortal soul or whether when I die it’s the end.”

This is a dialogue Larry has with his then-fiancee Isabel Bradley, who has agreed to let him live in France for the two years mentioned, to see, from her point of view, if he can get over the funk he has found himself in, come back to America to marry her and begin a career as a stockbroker in a prestigious firm.

A very respectable and proper set of expectations. But totally in conflict with Larry’s true aims, described, I suppose it should be parenthetically mentioned, in a set of themes and images that are eerily reminiscent of Hugh Conway in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, a 1933 novel I can only assume Maugham read before publishing The Razor’s Edge in 1944.

But, let’s get back to Isabel and Larry.

Isabel gave a little gasp. It made her uncomfortable to hear Larry say such things, and she was thankful that he spoke so lightly, in the tone of ordinary conversation, that it was possible for her to overcome her embarrassment.

“But Larry,” she smiled. “People have been asking those questions for thousands of years. If they could be answered, surely they’d have been answered by now.”

Larry chuckled.

“Don’t laugh as if I’d said something idiotic,” she said sharply.

“On the contrary I think you’ve said something shrewd. But on the other hand you might say that if men have been asking them for thousands of years it proves that they can’t help asking them and have to go on asking them. Besides, it’s not true that no one has found the answers. There are more answers than questions, and lots of people have found answers that were perfectly satisfactory for them. Old Ruysbroeck for instance.”

“Who was he?”

“Oh, just a guy I didn’t know at college,” Larry answered flippantly.

Isabel didn’t know what he meant, but passed on.

“It all sounds so adolescent to me. Those are the sort of things sophomores get excited about and then when they leave college they forget about them. They have to earn a living.”

They have to earn a living. Hark that. A major theme is developing there.

“I don’t blame them. You see, I’m in the happy position that I have enough money to live on. If I hadn’t I’d have had to do like everybody else and make money.”

“But doesn’t money mean anything to you?”

“Not a thing,” he grinned.

“How long d’you think all this is going to take you?”

“I wouldn’t know. Five years. Ten years.”

“And after that? What are you going to do with all this wisdom?”

“If I ever acquire wisdom I suppose I shall be wise enough to know what to do with it.”

Wisdom is only useful if one can “do” something with it. The theme continues to develop.

Isabel clasped her hands passionately and leant forward in her chair.

“You’re so wrong, Larry. You’re an American. Your place isn’t here. Your place is in America.”

Uh oh. Here it comes.

“I shall come back when I’m ready.”

“But you’re missing so much. How can you bear to sit here in a backwater just when we’re living through the most wonderful adventure the world has ever known? Europe’s finished. We’re the greatest, the most powerful people in the world. We’re going forward by leaps and bounds. We’ve got everything. It’s your duty to take part in the development of your country. You’ve forgotten, you don’t know how thrilling life is in America today. Are you sure you’re not doing this because you haven’t the courage to stand up to the work that’s before every American now? Oh, I know you’re working in a way, but isn’t it just an escape from your responsibilities? Is it more than just a sort of laborious idleness? What would happen to America if everyone shirked as you’re shirking?

And there it is. Probably as fully on display as Maugham dared to make it. In this one scene, we seem to have set before us the dramatic tension that will consume the rest of the narrative. Larry, representing the inner drive for spiritual truth and meaning, and Isabel, representing the cultural drive for wealth and domination, in conflict with one another, in society, and in Maugham’s soul. A reader should be excused for thinking that whichever character achieves happiness in the end will reveal Maugham’s bias in this eternal struggle.

Except, much of the novel isn’t actually about Larry Darrell. Much--too much, in my opinion--is about the petty obsessions that go with wealth and privilege. It’s typified by Isabel Bradley herself in an aspiring upper class kind of way, but even more fully developed in the character of an American expatriate living in Paris named Elliott Templeton.

If I have given the reader an impression that Elliott Templeton was a despicable character I have done him an injustice.

Those, of course, are Maugham’s words, not mine, and they come early, after several pages of character sketch and backstory, in which the author basically describes Templeton as a snob, a phony, and a gold digger.

He was for one thing what the French call serviable, a word for which, so far as I know, there is no exact equivalent in English. The dictionary tells me that serviceable in the sense of helpful, obliging, and kind is archaic. That is just what Elliott was. He was generous, and though early in his career he had doubtless showered flowers, candy, and presents on his acquaintance from an ulterior motive, he continued to do so when it was no longer necessary. It caused him pleasure to give. He was hospitable. His chef was as good as any in Paris and you could be sure at his table of having set before you the earliest delicacies of the season. His wine proved the excellence of his judgment. It is true that his guests were chosen for their social importance rather than because they were good company, but he took care to invite at least one or two for their powers of entertainment, so that his parties were almost always amusing. People laughed at him behind his back and called him a filthy snob, but nevertheless accepted his invitations with alacrity.

He is, I realized, having recently read a biography of Somerset Maugham, clearly patterned after Maugham himself--at least the Maugham who publicly resided in the South of France and entertained aristocrats and celebrities at his villa. Which is odd, of course, because Maugham himself is famously the first-person narrator of The Razor’s Edge. “I have never begun a novel with more misgiving,” the novel begins, and from those first words to the novel’s last, the presence of Maugham--as a character, as the narrator, as an author; or, indeed, as all three--is hopelessly intertwined.

So what is Maughan doing here? He’s hiding, clearly. Obviously in the narrator/character of Maugham, and less obviously in the character of Elliott Templeton. But I believe both of those are really meant just to keep you off the scent. Because Maugham, I suspect, is hiding most deeply of all in the character of Larry Darrell.

“It doesn’t surprise me that you don’t understand Larry,” I said, “because I’m pretty sure he doesn’t understand himself. If he’s reticent about his aims it may be that it’s because they’re obscure to him. Mind you, I hardly know him and this is only guesswork: isn’t it possible that he’s looking for something, but what it is he doesn’t know, and perhaps he isn’t even sure it’s there? Perhaps whatever it is that happened to him during the war has left him with a restlessness that won’t let him be. Don’t you think he may be pursuing an ideal that is hidden in a cloud of unknowing--like an astronomer looking for a star that only a mathematical calculation tells him exists?”

This is Maugham the character/narrator speaking to Isabel, but it is also Maugham the author speaking to the reader, revealing a dangerous truth that perhaps everything he has done, all the works he has written, have been in service of an ideal that he doesn’t know for sure is even there.

This is an exciting interpretation. And it probably requires another full read of the novel if I intend to develop it--here on my blog, or in one of those wistful PhD dissertations I actually think I may have time to write someday.

For example, when I complain that there is too much Elliott Templeton and not enough Larry Darrell in the novel, is that also Maugham telling me something about himself? Is he saying that he regrets all the time he has spent being like Templeton and longs, late in his life, for more of that time having been spent being like Larry?

And then, inevitably, we’ll have to deal with Charles Strickland.

“...What I’m trying to tell you is that there are men who are possessed by an urge so strong to do some particular thing that they can’t help themselves, they’ve got to do it. They’re prepared to sacrifice everything to satisfy their yearning.”

“Even the people who love them?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Is that anything more than plain selfishness?”

“I wouldn’t know,” I smiled.

The smile is the dead giveaway, for our course Maugham--Maugham the author, but here, even Maugham the character/narrator--does know. He, both of them, had already famously written about just such a character--and another of his alter egos.

Here’s how the second paragraph of The Razor’s Edge begins:

Many years ago I wrote a novel called The Moon and Sixpence. In that I took a famous painter, Paul Gauguin, and, using the novelist’s privilege, devised a number of incidents to illustrate the character I had created on the suggestions afforded me by the scanty facts I knew about the French artist. In the present book I have attempted to do nothing of the kind. I have invented nothing. To save embarrassment to people still living I have given to the persons who play a part in this story names of my own contriving, and I have in other ways taken pains to make sure that no one should recognize them.

Maugham’s painter in The Moon and Sixpence, Charles Strickland, is also a man “possessed by an urge so strong to do some particular thing”--paint--that he can’t help himself. He sacrifices everything to satisfy his yearning, even the people who love him. But Maugham, I think, goes out of his way to show that this isn’t plain selfishness. It is, he fears, the only way an artist can bring something great into the world.

In the exchange I most recently cited, Isabel is complaining to Maugham about Larry’s desire to learn Greek.

“What can be the possible use of Larry’s learning dead languages?”

“Some people have a disinterested desire for knowledge. It’s not an ignoble desire.”

“What’s the good of knowledge if you’re not going to do anything with it?”

“Perhaps he is. Perhaps it will be sufficient satisfaction merely to know, as it’s sufficient satisfaction to an artist to produce a work of art. And perhaps it’s only a step toward something further.”

The comparison to art is, I think, significant. If Larry Darrell is a kinder and gentler version of Charles Strickland, then he is much more deeply buried in a text preoccupied with the social graces and appearances that both rejected. In The Moon and Sixpence, Maugham fully embraced the misanthrope within. In The Razor’s Edge, he has screened that creature behind several layers of his own better sensibilities and those of most of us who find themselves approaching the text.

As I said, I think I need to read it again.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Labels:

Books Read

Monday, February 13, 2017

Be Sure to Thank Your Power Members

I recently drove 350 miles, one way, to visit a member of my association.

To be fair, it was more than just a "member visit." We're planning an activity in this member's community, they are helping to host and support it, and there were (and still are) a lot of logistical details that need to be identified and resolved. We got a great start on that business, but the trip provided me with another lesson of how important it is to get out of the four walls of my association office and visit my members in their natural environment.

Because of the timing of my arrival, the first thing we did was have lunch. I run a trade association, which means our members are companies, not individuals, and this company is one of our largest members, with their own cafeteria. As we sat around one of those common tables, in a room full of people, all employees of the member company, the small talk conversation perhaps naturally turned to the people I might know in the company.

You see, the folks I was meeting with were all relatively new to me. They were part of the planning group for the activity I described. So as I started listing off other people I knew in the company, it was reported to me where that person might be. Oh, he's in Europe today. Or, She's in. We should swing by and say hi. Or, Yes, he knows you're here today. He's going to try and come by our meeting later.

Then, the best thing happened. Someone I knew, but whose name I had forgotten to recite, walked by. I jumped up from the table and shook his hand. He was glad to see me. He hadn't been in the loop and hadn't known that I was going to be visiting.

It was then that I realized how many people I actually knew in the company--and, by extension, how deeply involved this company was in the activities of my association. This person is on our board, and that person chairs one of our committees. This person appeared in a promotional video our association produced, and that person comes to every education conference. This person relies on the market data reports we produce, and that person works within our standardization initiatives.

This company is not just a member of our association. It is a "power member," getting tremendous value out of the things we do and strongly supporting our initiatives and activities. I somewhat belatedly realized what a delight it was to have the opportunity to spend a day on their campus, greeting everyone I knew individually, and letting them know how much I appreciated their support.

Was it worth driving 700 miles in two days? Absolutely.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://appointmentschedulingnews.com/want-to-become-a-power-user/

To be fair, it was more than just a "member visit." We're planning an activity in this member's community, they are helping to host and support it, and there were (and still are) a lot of logistical details that need to be identified and resolved. We got a great start on that business, but the trip provided me with another lesson of how important it is to get out of the four walls of my association office and visit my members in their natural environment.

Because of the timing of my arrival, the first thing we did was have lunch. I run a trade association, which means our members are companies, not individuals, and this company is one of our largest members, with their own cafeteria. As we sat around one of those common tables, in a room full of people, all employees of the member company, the small talk conversation perhaps naturally turned to the people I might know in the company.

You see, the folks I was meeting with were all relatively new to me. They were part of the planning group for the activity I described. So as I started listing off other people I knew in the company, it was reported to me where that person might be. Oh, he's in Europe today. Or, She's in. We should swing by and say hi. Or, Yes, he knows you're here today. He's going to try and come by our meeting later.

Then, the best thing happened. Someone I knew, but whose name I had forgotten to recite, walked by. I jumped up from the table and shook his hand. He was glad to see me. He hadn't been in the loop and hadn't known that I was going to be visiting.

It was then that I realized how many people I actually knew in the company--and, by extension, how deeply involved this company was in the activities of my association. This person is on our board, and that person chairs one of our committees. This person appeared in a promotional video our association produced, and that person comes to every education conference. This person relies on the market data reports we produce, and that person works within our standardization initiatives.

This company is not just a member of our association. It is a "power member," getting tremendous value out of the things we do and strongly supporting our initiatives and activities. I somewhat belatedly realized what a delight it was to have the opportunity to spend a day on their campus, greeting everyone I knew individually, and letting them know how much I appreciated their support.

Was it worth driving 700 miles in two days? Absolutely.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://appointmentschedulingnews.com/want-to-become-a-power-user/

Labels:

Associations,

Member Engagement

Monday, February 6, 2017

Starting With the End in Mind

I recently had a great experience at the Winter Leadership Conference of the Council of Manufacturing Associations. I recently posted on the fact that I had been elected to their board, and it is experiences like this one that helped me decide to put my hat in that ring. Whatever I can do to help facilitate experiences like these for me and my peers, I'm all in.

It was in a session on "Industry Workforce Solutions." Nearly every staff executive in the room is facing the challenge of developing an educated workforce for the industries they represent. I know I am. Bouncing ideas, sharing successes, and raising red flags in such an environment is where I typically find the most educational value at these conferences. Take the outside expert off the stage and let me get into the problem solving trenches with my peers.

At one point, I asked the room a question. How many of you have a specific target for the number of students you're looking to educate? In my association, I told them, we're trying to define the scope of the problem so we can bring the right amount of resources to bear. For example, if we determine that there are 5,000 positions in our industry with a certain skill set, and we assume a 5% annual attrition rate among those positions, then we had better make sure that our programs, whatever they are, are producing 250 graduates with those skill sets each year, and that we're finding ways to connect those graduates to jobs in our industry. In other words, how many of you are starting with the end in mind?

Not a single hand in the room went up.

That really surprised me, but perhaps it shouldn't have. The discussion I described above is something we've just started having in my association, and we've been working on the educated workforce issue for more than 15 years now. Up until recently, the focus has only seemed to be on more, more, more.

How many educated workers do you need? More! How many grants and scholarships should we give? More! How much money should we spend? More, more, more!

I forget which of my board members said it, but a few board meetings ago, one of them forced the question. How much is enough? What are we trying to generate and how many resources should be dedicated to that purpose? It was a startling insight at our board table, just as I hope it was for some of my fellow staff executives at the CMA conference. Like most things we do, when it comes to creating an educated workforce, we have to start with the end in mind.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://tech.co/sell-your-tech-company-2014-09

It was in a session on "Industry Workforce Solutions." Nearly every staff executive in the room is facing the challenge of developing an educated workforce for the industries they represent. I know I am. Bouncing ideas, sharing successes, and raising red flags in such an environment is where I typically find the most educational value at these conferences. Take the outside expert off the stage and let me get into the problem solving trenches with my peers.

At one point, I asked the room a question. How many of you have a specific target for the number of students you're looking to educate? In my association, I told them, we're trying to define the scope of the problem so we can bring the right amount of resources to bear. For example, if we determine that there are 5,000 positions in our industry with a certain skill set, and we assume a 5% annual attrition rate among those positions, then we had better make sure that our programs, whatever they are, are producing 250 graduates with those skill sets each year, and that we're finding ways to connect those graduates to jobs in our industry. In other words, how many of you are starting with the end in mind?

Not a single hand in the room went up.

That really surprised me, but perhaps it shouldn't have. The discussion I described above is something we've just started having in my association, and we've been working on the educated workforce issue for more than 15 years now. Up until recently, the focus has only seemed to be on more, more, more.

How many educated workers do you need? More! How many grants and scholarships should we give? More! How much money should we spend? More, more, more!

I forget which of my board members said it, but a few board meetings ago, one of them forced the question. How much is enough? What are we trying to generate and how many resources should be dedicated to that purpose? It was a startling insight at our board table, just as I hope it was for some of my fellow staff executives at the CMA conference. Like most things we do, when it comes to creating an educated workforce, we have to start with the end in mind.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

Image Source

http://tech.co/sell-your-tech-company-2014-09

Labels:

Associations,

Workforce Development

Saturday, February 4, 2017

On Many a Bloody Field by Alan D. Gaff

“Four Years in the Iron Brigade” is the subtitle here, and that’s a fair summary, this being essentially a regimental history of the 19th Indiana Volunteers, following that regiment and the men that comprised it through the four bloody years of the American Civil War.

And early on I had some concerns.

Resolved, That, from the troubled condition of our native land, and the possibility of a disgrace to the Flag we have worshipped as the emblem of Peace, Liberty and Justice, we believe it to be the duty of all American citizens to defend it, and more particularly, we who are in the prime of life, with none of the ties which bind those of more advanced age. We, therefore, resolve to tender our services to the Governor of the State of Indiana, in case our services are required, in the subjugation of those who have forgotten the noble blood of our revolutionary Fathers, which was spilled in the establishment of this, the greatest and freest government since the existence of man, and whose flag has been disgraced, for the first time, by those who should have died in its defense.

This is the text of a resolution, written by one and approved by all the members of one of the formative volunteer units that would soon be consolidated with others to become the 19th Indiana, and published in a local paper. Written and endorsed by idealistic young men who have never been to war, it is clearly written more for posterity than for the pressing realities of the present. And as I read it, early in Gaff’s narrative, I couldn’t help but wonder what kind of reporter Gaff would be. Would he follow this early example, emphasizing the patina of patriotic glory covering the historical events he would relate, or would he, as the young men in the 19th Indiana inevitably would, descend into the murky moralistic muck of actual war?

A hundred pages later, and the men of the 19th Indiana have not yet seen any real combat, navigating instead the politics of regimental organization and leadership. Here, when the Colonel forces out the elected Lieutenant Colonel for one of his “true friends,” the enlisted men pitch in to buy the departing officer a commemorative sword.

The regiment was formed in a hollow square with [Lieutenant Colonel Robert] Cameron, the Stars and Stripes, and the regimental colors in the middle. Sergeant George H. Finney, of Company H, came forward with the sword and made a few remarks:

“Accept this sword from your friends, through me. Wear it, and wherever it goes, let me assure you there is not a ‘wild Hoosier’ but will follow. May that blade ever be found fighting in defence of our glorious old banner, till not a rebel dare raise his arm to assail its sacred folds. May you be spared to see the end of this unparalleled war, and enjoy the blessings of that peace which your valor will have aided in establishing. May the ‘Red, White and Blue’ again flaunt joyously over city, town and hamlet, from the snow-capped hills of Maine to the golden plains of California--from the peninsula of Florida to the remotest bounds of Oregon. These our heart-felt prayers accompany this emblem of esteem. And when in coming years you gaze upon this trusty weapon, perchance dimmed by rust, remember that it is a token of kindly feeling from your fellow soldiers.”

Not bad for a few evidently extemporaneous remarks, eh?

Cameron graciously accepted the gift and, “filled with inexpressible emotions,” made the following reply:

“I feel doubly proud of this beautiful blade, coming, as it does, from one of the noblest bands of men any cause ever enlisted together--men who left their homes and firesides, their wives and little ones, and the idols of their souls, to rally around their country’s insulated flag, to render safe a time-honored Constitution and a glorious Union, who, despising all danger, all hunger, fatigue and cold, thought of nothing but how they could save their country.”

This, remember, to a group of men who had yet to experience any real combat. At this stage of the narrative, I’m still thinking about how Gaff is going to handle things when the bullets start flying around and through these men’s heads.

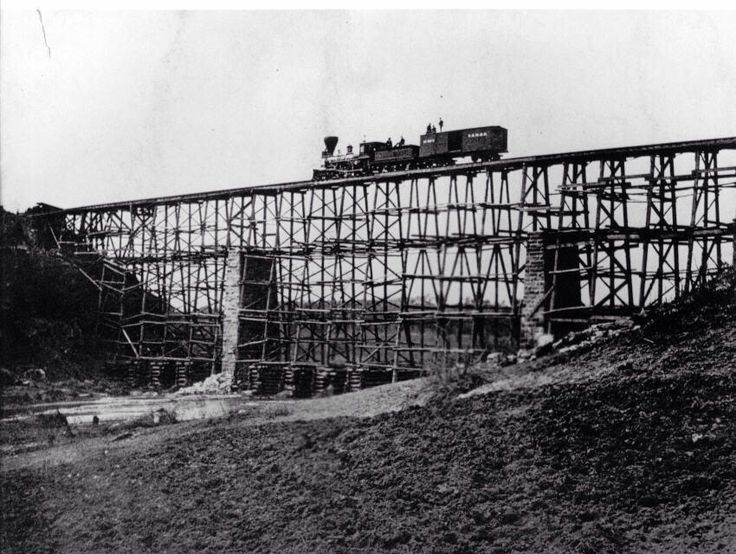

Now, given how long ago it happened, and given the frenetic pace of technological advancement in our current society, it is sometimes easy to forget that the Civil War itself was a time of tremendous progress and innovation. It was the first major war fought in which railroads played a key role in the movement of both men and material, for example, and that is an area of innovation in which the Union excelled. And before the 19th Indiana found itself in its first battle, the regiment played a small part in that much larger story.

The most formidable obstacle on the railroad line was at Potomac Creek, where the bridge had been burned [by retreating Confederates]. On May 1st [1862], ten men from each company in the 19th Indiana, the whole commanded by Lieutenant Benjamin Harter of Company K, reported for duty as bridge builders. Similar details were furnished by the 6th and 7th Wisconsin regiments [other regiments in what would come to be called the Iron Brigade]. Colonel [Herman] Haupt was unimpressed with his construction crew and complained that:

“many of the men were sickly and inefficient, others were required for guard duty, and it was seldom that more than 100 to 120 men could be found fit for service, of whom a still smaller number were really efficient, and very few were able or willing to climb about on ropes and poles at an elevation of eighty feet.”

Despite his untrained crew, lack of tools, and several days of wet weather, the Potomac Creek bridge was completed in less than two weeks.

Haupt’s bridge was an engineering marvel. It spanned a chasm nearly 400 feet wide and towered 80 feet above the creek’s surface. Built of unhewn trees and saplings cut in the neighboring woods, the bridge would carry ten to fifteen trains a day for several years. One engineer estimated that if all the timber were laid end to end it would stretch nearly seven miles. When President Lincoln saw the bridge while visiting [General Irvin] McDowell’s command, he declared it to be “the most remarkable structure that human eyes ever rested upon.” He also said that it appeared to be built entirely of “beanpoles and cornstalks.”

Engineering advances such as this were also reflected on the battlefields of the Civil War, where the artform of slaughtering men frequently reached an apogee never before approached. And actually experiencing this meatgrinder had a predictable effect on the soldiers who had mustered in with the heart-swelling expectations of glory and patriotism. And when it occurs, much to Gaff’s credit, he doesn’t shy away from this important and transformative part of the regiment’s history.

The 19th Indiana got their first taste of actual war at Brawner’s Farm in the Battle of Second Bull Run (or Manassas).

Both officers and enlisted men searched for some meaning to their first real combat experience, but there was none to be found. Their sacrifice had gained nothing for the cause. Consequently, indignation and ill will toward their generals, who had abandoned the Brawner Heights and allowed the enemy to occupy that position, became widespread. Major Rufus Dawes wrote bitterly, “The best blood of Wisconsin and Indiana was poured out like water, and it was spilled for naught.” Captain Patrick Hart called the affair “a useless slaughter of brave Indianians.” After listening to numerous tales by the Hoosiers, W. T. Dennis declared that [brigade commander General John] Gibbon’s losses were “damning evidences of the treachery or stupidity of [corps commander General Irvin] McDowell.” The soldiers expressed their own displeasure on the morning of August 29th [1862], when they greeted [division commander] General [Rufus] King with a chorus of groans and boos.

Welcome to war, lads. Even the generals who know what they’re doing (and many in the Civil War didn’t) can’t protect you from the shifting tides of battle. Indeed, it’s not even their job to protect you. It’s there job to use you--whether they know how or not--to stem tides that exist in the battlefields of both their war and their minds.

But, of course, it was worse than that.

Back on King’s abandoned battlefield, the glaring sun illuminated a ghastly spectacle on the morning of August 29th. The Brawner farmhouse and its outbuildings, now quite perforated with musket balls, sat as quiet sentinels overlooking the bloodstained land. Hundreds of bodies, clothed in both blue and butternut, lay scattered across the Virginia fields. In some places, a person could walk for several yards on the corpses. At a fence near the house, the bodies of several Hoosiers, now riddled with lead, hung on the rails where they had died. Even farm animals had been shot to death in their pens, while the bodies of rabbits and birds lay in the grass, innocent victims of the relentless musketry. Hundreds of wounded, overlooked during the night, groaned in pain and cried constantly for water. The stench of gunpowder and blood and human waste hung like a cloud over the battlefield. The sight was enough to sicken one’s soul.

Indeed. But it would actually get even worse than this. That was the scene on the morning after the battle. Let’s roll forward nine more days.

By that time the Bull Run battlefield was a horrid place. Looking out from the ambulances as they passed along, King’s men could see hundreds of unburied Union soldiers lying stark naked or stripped to their underclothing by the rebs. Ten days before they had been brave and jaunty soldiers. Now they lay “swollen, blistered, discolored to the blackness of Ethiopians in most instances, and emitting odors so thick and powerful that it seemed that they might have been felt by the naked hand.” Maggots crawled in their eyes, ears, mouths, noses and hideous wounds. Wounded Hoosiers must have considered themselves lucky indeed to have avoided such a fate.

Lucky? I suppose so. But I’m sure thoughts other than, “Gee, ain’t I Iucky,” occurred to some of those wounded and surviving soldiers. Thoughts about the utter random madness of it all.

A little more than ten months later, the men who survived Second Manassas would find themselves fighting 100 miles north at Gettysburg. On July 1, 1863, the 19th Indiana was heavily involved in battling Confederates on McPherson’s Ridge.

All the dead and badly wounded were necessarily left behind. [24th Michigan] Colonel [Henry] Morrow commended the neighboring Hoosiers, who “maintained their first line of battle, until their dead were so thick upon the ground that you might step from one dead body to another.” By now the entire color guard had been killed or wounded. As the regiment began to fall back, someone yelled to Lieutenant Macy that the flag was down. He shouted back, “Go and get it!” The reply was, “Go to hell, I won’t do it!” Macy and First Sergeant Crockett East, Company K, ran back and tried to put the blue silk flag in its case, but East was shot dead and fell on it. Macy pulled the stained silk from under East’s body and started up the hill. Burr Clifford, Company F, threw down his musket and accoutrements and took the flag, noticing that the banner had also fallen. He started back, but stopped to furl the colors so that “they would not make so conspicuous a mark.” Holding the state flag in his left hand and turning sideways to minimize his exposure, Clifford became the target for rebel muskets:

“almost instantly a Bullitt struck the staff below my hand an other struck my hat an other the left leg just cutting my pants below my knee, an other the right leg just above the knee cutting the pant, also two others cut the tail of my Blouse in the rear.”

Seeing no officer nearby, Clifford prudently started back up the hill with the state flag.

I know that many see heroic patriotism in stories like these--men fighting for the honor of carrying their regiment’s flag when doing so means almost certain death. But frankly, all I see is the utter madness of a mass psychosis. To my way of thinking, the rational mind resides in the man who said “Go to hell, I won’t do it!” All else is folly. But read on.

Sergeant Major Asa Blanchard had requested and been assigned the duty of detailing replacements from the ranks as color bearers fell, killed or wounded. The lieutenant colonel [William Dudley] saw this desperate situation and the “almost impossibility of getting men from the decimated ranks to discharge the fatal duty as fast as necessary” and ran to help. While Blanchard went after another volunteer, Dudley held the Stars and Stripes “long enough to meet the fate of all who touched it that day.” A minie ball struck Dudley’s right leg midway between ankle and knee, shattering the fibula. In a letter to Blanchard’s sister, Dudley described what followed:

“As I lay there with the staff in my hand your brother, his voice trembling with feeling, took the staff from my hand, and giving it to a soldier he had detailed, assisted me back from the line a few feet and said: ‘Colonel, you shouldn’t have done this. That was my duty. I shall never forgive myself for letting you touch that flag.’ He called to two slightly wounded soldiers and bade them get me out of the fire, and as he left he turned and smilingly said, “It’s down again, Colonel. Now it’s my turn.”

Two men dragged Dudley back over the crest, leaving a bloody smear form his leg in their wake. While removing the crippled officer, one of his bearers was struck by a ball that had glanced off Dudley’s side.

Imagine the scene. Like something out of a nightmare. Death swirling around in the air like supersonic hornets, men falling, bleeding, crying, dying all around, and amidst all the sound and the fury, Sergeant Major Asa Blanchard, smiling, and turning dutifully to face the unforgiving storm.

Later...

When Blanchard saw Burr Clifford walking up the ridge, he ran up, demanded to know why he was running away with the colors and snatched them from his hands. Asa unfurled the flag and began waving it vigorously. Private William R. Moore, Company K, now had the Stars and Stripes, but a bullet took off the index finger of his left hand. …

Blanchard was waving his flag and crying out “Rally, boys,” when a minie ball severed an artery in his groin. Burr Clifford stepped aside to avoid blood spurting from the wound and William Jackson, who stood next to Blanchard, watched in horror as his life gushed away. When Clifford reached for the flag, Blanchard managed to blurt out, “Don’t stop for me. Don’t let them have the flag.” Then with his dying breath, Asa murmured, “Tell mother I never faltered.”

There is madness here--a frenzied madness that can consume the patriotism and thirst for glory that young men bring with them to war and transform it into a kind of cultural hero worship, but it is madness all the same. The rational man is innately prejudiced against sacrificing his own life and taking the lives of others, but when thrown repeatedly into the kind of circumstances confronted by the men of 19th Indiana, those prejudices can be suppressed and replaced with a conviction of justice and reverence for the very acts once thought abhorrent.

But not all rational men will so succumb. After Chancellorsville (and before the events just described at Gettysburg), the men of the 19th Indiana had an experience that would test their limits of this understanding.

The victorious rebel army had started north, perhaps contemplating another invasion of Maryland, so the 19th Indiana was up and marching before daylight on June 12th [1863]. Despite the urgency of their march, after lunch the entire division formed up to witness an exceptional sight. Private John P. Woods, Company F, 19th Indiana, was to be shot to death with musketry. He had been found guilty of desertion for running away on the morning the Iron Brigade charged across the river at Fitzhugh Crossing. This was his third such offense. He had deserted first at Rappahannock Station on August 20, 1862, and remained absent until November 17th. His second absence occurred at Fredericksburg, but he had managed to convince a court-martial of his innocence. He would not run away again.

Shocking, isn’t it? Running away in the face of the enemy. Three times! Clearly a coward. Someone to make an example of. As reported, he had been tried by a second court-martial, and this one had found him guilty.

Private Woods offered no testimony in his defense, although he did make an oral statement:

“The reason I left the regiment before crossing the river near Fredericksburg was because I did not want to go in a fight. I cant fight. I cannot stand it to fight. I am ashamed to make the statement, but I may as well do it now as at any other time. I never could stand a fight. I never could bear to shoot any body. I have done my duty in every way but fight. I have tried to do it but cannot. I am perfectly willing to work all my lifetime for the United States in any other way but fight. I have tried to do it but cannot. I went to my doctor when I left the regiment and wanted him to give me a pass and I would go and work and wait on the wounded in the hospital. he told me that he guessed he had enough. I had better go on and try to do my duty. he said he would see about it. I could not find out where the hospital was. he had not stationed it. then after a while I came to the conclusion I would try to go home. I started to go to Aquia Creek landing and got lost on my way and got outside of our picket lines, out by Stafford Court House. I met the pickets there and came on to our own pickets and gave myself up. I had been acquainted in Tennessee and I gave myself up as a rebel. I made the statement for fear they would think I was a bushwhacker. then I was sent on under arms until they received me here. I am willing to do all I could do for my country. I like it as much as anybody does. I was always willing to try to fight for my country, but I never could. I am willing to try to fight for it again. I am ashamed of my conduct and will always try to do better hereafter.”

I don’t know what you see here, but I see a man of rational conscience, doing the best he can under extremely trying circumstances. I know that when the world has gone mad with something--with war, in the case, but often with other things as well--it is the people who stand apart that seem to be the crazy ones. But they are not. Just because your government and your society tells you it is okay to kill people, it does not make it so. The way most people are wired, with those kind of permissions granted, they’ll take up the gun and blaze away, likely to feel horrible remorse when the deed is done. Others will adamantly refuse, and damn the consequences, knowing that they are sane and the world around them is crazy. And others still, probably the lowest percentage all, others like Private John P. Woods, Company F, 19th Indiana, will simply and innocently just be incapable of the violence required of them.

Often, how a man like this meets his death is as illustrative to those around him as the way he had tried to lead his life.

The prisoner was turned over to Clayton Rogers, [division commander General James] Wadsworth’s provost marshal, who found Woods to be “a simple-minded soldier, without any force or decision of character.” Chaplain Samuel Eaton, 7th Wisconsin, spent June 11th with the condemned man and found him to be holding up well. Eaton wrote, “His firmness, composure and naturalness is astonishing. He does not complain or whine or cry; says he is not afraid to die.” The chaplain kindly gave Woods seven small tracts to read, so that his father and each of his brothers and sisters could have a memento after his death. While Reverend Eaton talked with Woods, the provost marshal assembled a guard detail, put together a twelve-man firing party and had a rude coffin constructed.

When Wadsworth’s division marched on the 12th, Woods, handcuffed and with shackles on his feet, rode behind in an ambulance. After completing their noon meal …

The needs of the living ever present even in the very face of death.

… the Iron Brigade and Lysander Cutler’s brigade marched into position around a hastily dug grave and the soldiers stacked arms. General Wadsworth and his staff, all mounted, waited for the prisoner, while curious men …

Oddly curious about this death among the thousands of others they had undoubtedly witnessed.

… from other commands collected outside the formation. His coffin was placed by the grave, then Woods stepped down from the ambulance and knelt in prayer with the chaplain for a few minutes. Moving with a “sturdy step” to his coffin, he took off his hat, placed it upon the ground and sat down on the rough wooden box. Woods asked that he not be blindfolded, but Lieutenant Roger said it must be done …

For whose benefit, I wonder, the condemned or those who condemned him?

… and tied a handkerchief around his head. The condemned man’s last view of this world was of twelve stern-faced men with muskets, his executioners.

This firing party “manifested more uneasiness than the criminal.” The twelve men were addressed by Wadsworth, then received their muskets, one of which contained a blank charge. This would, in theory, allow each man to imagine that he had fired a blank round, but experienced troops could easily tell the difference. …

And who but experienced troops are put into a firing squad? Shooting a fellow soldier is not generally something they asked you to do on your first day in the army. And if experienced, why bother with the blank round subterfuge? Don’t they all agree Woods deserves to die? Perhaps more or perhaps less than Johnny Reb.

… As they filed into line thirty feet in front of their target, the firing party must have been impressed with Woods’s composure. Others certainly were. Jeff Wasson said “he took it very cool” and a 7th Indiana man remembered, “He seemed to be as calm as though his end was not so near.” A Badger noticed that Woods sat on his coffin “as one would take a seat before a camera.” Sergeant Sullivan Green, 24th Michigan, thought he detected a slight shudder after Lieutenant Rogers tied the blindfold, but no other soldier mentioned any similar reaction.

As Rogers gave the command, “Ready!” one Badger imagined, “What a moment it must have been to the unfortunate victim who heard that awful click, the prelude to the last sound he was to hear on earth!” At the command, “Aim!” Woods did not move a muscle. When Lieutenant Rogers commanded “Fire!” eight muskets …

Eight? Why not twelve?

… on the right of the line roared an answer and Woods toppled backwards over his coffin. But the firing party had aimed low, only four bullets hitting him, and he still lived. The next two men advanced to within three feet and administered the coup de grace. Wadsworth’s medical director examined Woods and pronounced him dead. The lifeless corpse was lifted into its coffin, placed in the hole and covered over with dirt.

Poignant. And clearly affecting to those who witnessed it. But here’s where the story gets really interesting.

There was a strong reaction to Woods’s execution. Lieutenant George Breck, an officer in the division artillery, wrote: “Better a thousand times that he should have fallen on the battlefield than have fallen in this ignoble way.” A 7th Indiana man meditated: “In perfect health and with his friends and the next minute in eternity. What a warning, let us hope that not very many of those who witnessed the execution needed such a warning.” Another Hoosier wrote that it was a “very useful” example since desertions were so common. Jeff Wasson prefaced his description of the event by stating: “I hope never to witness the like again while in the service.”

Rumors about the affair began circulating almost immediately. One the 14th Brooklyn boys remembered:

“It was said that Wood had a wife at home, back in Indiana, who was lying desperately ill. As he marched he brooded over the possibility of her dying without seeing him again. He applied for a furlough, but the furlough was refused to him. The more he brooded, the more he determined to see her at all costs. He therefore deserted, expecting to return to his duty afterwards.”

Orville Thompson of the 7th Indiana heard a different story: “The sympathetic part came in an hour later when his aged father came to head-quarters bringing a pardon signed by President Lincoln.” Another version of this story told of an officer and citizen arriving just five minutes after the execution with a message from Lincoln commuting the sentence of death to life imprisonment. Yet a third variation claimed that an officer arrived with a reprieve just as Woods had expected to hear the command to fire. He fell back upon his coffin, “apparently dead,” but the great strain and instant release had left him “a hopeless maniac.” This last version claimed that the whole event, “a fearful ordeal for the deserter,” had been staged to make an impression upon the brigade. These rumors seemed to exonerate Woods, making his death some sort of huge mistake by the army bureaucrats.

This reveals a fascinating psychology. First, madness destroys the wisdom it finds in its midst, and then it struggles to reconcile the magnitude of its crime.

Eventually, of course, wisdom prevails over madness--a kind of earned wisdom that apparently requires the crucible of madness to be acquired. In the end, Gaff summarizes this earned wisdom well, with only a touch of hyperbole. The war is over, and the surviving members of that first volunteer unit, the Richmond City Greys, are going home.

As their train pulled out of the Indiana Central depot and headed for Richmond, the returning soldiers could not help but think back to when the City Greys started for Indianapolis to save the nation from Southern rebels. What a difference four years had made on them. In 1861 these volunteers had no inkling of what this war would be like. Their knowledge of war was confined to books that had glorified America’s previous conflicts, fanciful patriotic engravings, and tales of neighbors who had served briefly in the Mexican War. These naive recruits were stirred by the sight of prancing horses and plumed hats, accompanied by the squeaking of fifes and the beating of drums. The boys were in the prime of their lives, eager to prove themselves in this greatest of adventures. There was glory to be won and the train ride from Richmond to Indianapolis seemed liked the beginning of a holy crusade against traitors who sought to destroy the country.

These weary men must surely have smiled at that recollection of their youthful enthusiasm in 1861. Four years later, these veterans of the Iron Brigade were well aware of the cost of winning the war and preserving the nation. They had charged time after time into musketry hotter than a thousand Julys, had spit repeatedly in Death’s face and had somehow, miraculously, emerged alive from the trauma that gutted a generation of American youth. They had seen firsthand the waste, the overwhelming waste of human life and property and resources. Historians would later write of glory, but the soldiers, from a unique perspective gained with the burial parties, saw only murder on a massive scale.

Murder on a massive scale. If only current and future generations could approach the prospect of war with the wisdom seemingly only gained by those who have survived it.

+ + +

This post first appeared on Eric Lanke's blog, an association executive and author. You can follow him on Twitter @ericlanke or contact him at eric.lanke@gmail.com.

And early on I had some concerns.

Resolved, That, from the troubled condition of our native land, and the possibility of a disgrace to the Flag we have worshipped as the emblem of Peace, Liberty and Justice, we believe it to be the duty of all American citizens to defend it, and more particularly, we who are in the prime of life, with none of the ties which bind those of more advanced age. We, therefore, resolve to tender our services to the Governor of the State of Indiana, in case our services are required, in the subjugation of those who have forgotten the noble blood of our revolutionary Fathers, which was spilled in the establishment of this, the greatest and freest government since the existence of man, and whose flag has been disgraced, for the first time, by those who should have died in its defense.

This is the text of a resolution, written by one and approved by all the members of one of the formative volunteer units that would soon be consolidated with others to become the 19th Indiana, and published in a local paper. Written and endorsed by idealistic young men who have never been to war, it is clearly written more for posterity than for the pressing realities of the present. And as I read it, early in Gaff’s narrative, I couldn’t help but wonder what kind of reporter Gaff would be. Would he follow this early example, emphasizing the patina of patriotic glory covering the historical events he would relate, or would he, as the young men in the 19th Indiana inevitably would, descend into the murky moralistic muck of actual war?

A hundred pages later, and the men of the 19th Indiana have not yet seen any real combat, navigating instead the politics of regimental organization and leadership. Here, when the Colonel forces out the elected Lieutenant Colonel for one of his “true friends,” the enlisted men pitch in to buy the departing officer a commemorative sword.

The regiment was formed in a hollow square with [Lieutenant Colonel Robert] Cameron, the Stars and Stripes, and the regimental colors in the middle. Sergeant George H. Finney, of Company H, came forward with the sword and made a few remarks:

“Accept this sword from your friends, through me. Wear it, and wherever it goes, let me assure you there is not a ‘wild Hoosier’ but will follow. May that blade ever be found fighting in defence of our glorious old banner, till not a rebel dare raise his arm to assail its sacred folds. May you be spared to see the end of this unparalleled war, and enjoy the blessings of that peace which your valor will have aided in establishing. May the ‘Red, White and Blue’ again flaunt joyously over city, town and hamlet, from the snow-capped hills of Maine to the golden plains of California--from the peninsula of Florida to the remotest bounds of Oregon. These our heart-felt prayers accompany this emblem of esteem. And when in coming years you gaze upon this trusty weapon, perchance dimmed by rust, remember that it is a token of kindly feeling from your fellow soldiers.”

Not bad for a few evidently extemporaneous remarks, eh?

Cameron graciously accepted the gift and, “filled with inexpressible emotions,” made the following reply:

“I feel doubly proud of this beautiful blade, coming, as it does, from one of the noblest bands of men any cause ever enlisted together--men who left their homes and firesides, their wives and little ones, and the idols of their souls, to rally around their country’s insulated flag, to render safe a time-honored Constitution and a glorious Union, who, despising all danger, all hunger, fatigue and cold, thought of nothing but how they could save their country.”

This, remember, to a group of men who had yet to experience any real combat. At this stage of the narrative, I’m still thinking about how Gaff is going to handle things when the bullets start flying around and through these men’s heads.

Now, given how long ago it happened, and given the frenetic pace of technological advancement in our current society, it is sometimes easy to forget that the Civil War itself was a time of tremendous progress and innovation. It was the first major war fought in which railroads played a key role in the movement of both men and material, for example, and that is an area of innovation in which the Union excelled. And before the 19th Indiana found itself in its first battle, the regiment played a small part in that much larger story.

The most formidable obstacle on the railroad line was at Potomac Creek, where the bridge had been burned [by retreating Confederates]. On May 1st [1862], ten men from each company in the 19th Indiana, the whole commanded by Lieutenant Benjamin Harter of Company K, reported for duty as bridge builders. Similar details were furnished by the 6th and 7th Wisconsin regiments [other regiments in what would come to be called the Iron Brigade]. Colonel [Herman] Haupt was unimpressed with his construction crew and complained that:

“many of the men were sickly and inefficient, others were required for guard duty, and it was seldom that more than 100 to 120 men could be found fit for service, of whom a still smaller number were really efficient, and very few were able or willing to climb about on ropes and poles at an elevation of eighty feet.”

Despite his untrained crew, lack of tools, and several days of wet weather, the Potomac Creek bridge was completed in less than two weeks.

Haupt’s bridge was an engineering marvel. It spanned a chasm nearly 400 feet wide and towered 80 feet above the creek’s surface. Built of unhewn trees and saplings cut in the neighboring woods, the bridge would carry ten to fifteen trains a day for several years. One engineer estimated that if all the timber were laid end to end it would stretch nearly seven miles. When President Lincoln saw the bridge while visiting [General Irvin] McDowell’s command, he declared it to be “the most remarkable structure that human eyes ever rested upon.” He also said that it appeared to be built entirely of “beanpoles and cornstalks.”

Engineering advances such as this were also reflected on the battlefields of the Civil War, where the artform of slaughtering men frequently reached an apogee never before approached. And actually experiencing this meatgrinder had a predictable effect on the soldiers who had mustered in with the heart-swelling expectations of glory and patriotism. And when it occurs, much to Gaff’s credit, he doesn’t shy away from this important and transformative part of the regiment’s history.

The 19th Indiana got their first taste of actual war at Brawner’s Farm in the Battle of Second Bull Run (or Manassas).

Both officers and enlisted men searched for some meaning to their first real combat experience, but there was none to be found. Their sacrifice had gained nothing for the cause. Consequently, indignation and ill will toward their generals, who had abandoned the Brawner Heights and allowed the enemy to occupy that position, became widespread. Major Rufus Dawes wrote bitterly, “The best blood of Wisconsin and Indiana was poured out like water, and it was spilled for naught.” Captain Patrick Hart called the affair “a useless slaughter of brave Indianians.” After listening to numerous tales by the Hoosiers, W. T. Dennis declared that [brigade commander General John] Gibbon’s losses were “damning evidences of the treachery or stupidity of [corps commander General Irvin] McDowell.” The soldiers expressed their own displeasure on the morning of August 29th [1862], when they greeted [division commander] General [Rufus] King with a chorus of groans and boos.

Welcome to war, lads. Even the generals who know what they’re doing (and many in the Civil War didn’t) can’t protect you from the shifting tides of battle. Indeed, it’s not even their job to protect you. It’s there job to use you--whether they know how or not--to stem tides that exist in the battlefields of both their war and their minds.

But, of course, it was worse than that.

Back on King’s abandoned battlefield, the glaring sun illuminated a ghastly spectacle on the morning of August 29th. The Brawner farmhouse and its outbuildings, now quite perforated with musket balls, sat as quiet sentinels overlooking the bloodstained land. Hundreds of bodies, clothed in both blue and butternut, lay scattered across the Virginia fields. In some places, a person could walk for several yards on the corpses. At a fence near the house, the bodies of several Hoosiers, now riddled with lead, hung on the rails where they had died. Even farm animals had been shot to death in their pens, while the bodies of rabbits and birds lay in the grass, innocent victims of the relentless musketry. Hundreds of wounded, overlooked during the night, groaned in pain and cried constantly for water. The stench of gunpowder and blood and human waste hung like a cloud over the battlefield. The sight was enough to sicken one’s soul.

Indeed. But it would actually get even worse than this. That was the scene on the morning after the battle. Let’s roll forward nine more days.

By that time the Bull Run battlefield was a horrid place. Looking out from the ambulances as they passed along, King’s men could see hundreds of unburied Union soldiers lying stark naked or stripped to their underclothing by the rebs. Ten days before they had been brave and jaunty soldiers. Now they lay “swollen, blistered, discolored to the blackness of Ethiopians in most instances, and emitting odors so thick and powerful that it seemed that they might have been felt by the naked hand.” Maggots crawled in their eyes, ears, mouths, noses and hideous wounds. Wounded Hoosiers must have considered themselves lucky indeed to have avoided such a fate.